Intended Audience: Readers who are interested in contemporary colonialism, social justice, ethics, and the relationship between Christian thought and theology to the present-day state of Israel. (Note: I usually don’t do this, but to highlight particularly important points, I bold certain sentences and paragraphs).

Introduction

The Palestinian-Israel clash is once again in the news cycle, as violence has flared up in the form of bombing and rocket attacks. And since defenseless women and children are being killed day by day before, during, and after the attacks and cease-fire, those with any concern for justice, peace, and common humanity find themselves stirred to take sides (as they should) and take some form of action (as they also should).

I want to briefly tell my story about why I stand in solidarity with Palestinians, as an American citizen, as a Christian, as a scholar of religion (…and also as a decent human being who cares for those vulnerable people on our planet who are needlessly suffering). Because support for Israel was such an ongoing part of my religious life—from teenage years to (reluctantly) a 2013 Zionist tour of the Holy Lands—I’ve been forced to take some detours in my academic career to get a firmer grasp on both Christian theology on this subject and Middle-Eastern history.

My position today and reasoning for it isn’t original: I stand in solidarity for Palestinians because they (as a whole, we’re talking millions of people) are suffering unjust oppression (1) as war refugees, (2) under military occupation, and (3) trapped in an apartheid state without much hope for improving their lives—(4) all with the hearty support of millions of Americans and evangelical Christians (financially, economically, socially, politically, and religiously). If you don’t see a problem with this, I don’t know what to say.

My general view is the same as fellow scholar and anarcho-syndicalist Noam Chomsky:

Many, perhaps most people, don’t even know what events Chomsky is referring to. So I’m going to try and explain all of that (and much more) in this essay.

Many, perhaps most people, don’t even know what events Chomsky is referring to. So I’m going to try and explain all of that (and much more) in this essay.

Solidarity for Palestinians is roughly the same kind of solidarity and support I maintain with indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada (settler-colonialist states), who have also been conquered, then blamed and scapegoated, and then further oppressed—such as the Lakota here in the Black Hills. Of course, with Palestinians today, it’s far worse (in some ways, not all) than Native Americans living on the reservation. They’re geographically trapped and have limitations on their water and food supply. But the situation is similar to the Natives and indigenous reservations in that (1) they want their land back, and official laws recognize that right (e.g. Supreme Court for the Lakota in Black Hills, the UN for Palestinians), and (2) want to stop being continually harassed/oppressed/killed by the colonizer.

On that basic level, it’s not complicated. Renowned Chef Anthony Bourdain understood it clearly after a single trip to Gaza:

Those who have suffered incredible injustice need support in particular ways and particular times. Throughout much of history and still today, we (the privileged, protected, and/or powerful) can and should protect Jewish people/Judeans (academics sometimes use “Judeans” instead of “Jews” to avoid race theory and sometimes loaded connotations of “the Jews”; I will usually use “Judeans” and “Jewish people”) for the same reasons; they have undergone extensive persecution and oppression before and after the holocaust. When we say something like “Palestinian Lives Matter,” or “Black Lives Matter,” we do so because of past patterns and pressing current conditions, just as we would say “hey! That person’s house is on fire and needs attention!” We do not say “All Houses Matter!” in response, because that would be…stupid. It is a given that all people’s houses are worth something; saying this misses the point that the house on fire needs serious attention right now.

Expressing solidarity for the oppressed also intentionally disregards things like skin color and religious affiliation; especially in these kinds of desperate and dehumanizing situations, being human is what matters most. This is a point the Hebrew prophets make, whether its Israel’s treatment of others, or others’ treatment of Israel.

And it also doesn’t even matter what some political authorities say and do, as that often does not reflect what the people would have happen. In other words, what governments and political parties do is not necessarily a reflection of what its people want. In my own life, little of what the American government does is a representation of my will. When we look at a history of conflict and violence, we must grant the same possibility to those parties we are talking about, whether Arabs and Muslims, Judeans, atheists, or Christians, or whatever. We must distinguish ordinary people just trying to live their lives at home and the authorities that rule over them as a public face and overlording authority.

Much has happened since I last picked up this subject about a decade ago, including the publication of several important works of Palestinian history (e.g., Khalidi 2020; Masalha 2020; see bibliography at the end of this essay). After my transformative experience in college (though I was still a conservative evangelical at that time), I taught a series of classes at my hometown church (First Baptist) on the subject because of how central the “Israel” issue was, and because of how terribly skewed the discourse had become, and because of how bad Islamophobia is in evangelicalism. I remember sitting in my pastor’s office and asking him the question, “Is it possible for Jewish people in Israel to sin today, like if they killed other people?”, and my pastor said, “That’s a good question.”

You know you’ve really missed something when pastors (of all people) find it difficult to condemn murder just in the abstract!

But hey, just recently, the State Department rep of the U.S. was pressed with a similar question, and he, too, wasn’t sure what to say! (See at 3:45):

Zionism

I grew up on the John Hagee Prophecy Study Bible. (For some of you reading, I must clarify that this is a fact, not a joke!) If there was one book on the planet that would indoctrinate me to be an unconditional fanatically religious supporter of the modern day state of Israel, that would probably be it.

Hagee founded the mega-Cornerstone Church in San Antonio Texas the year I was born (1987) and later founded Christians United for Israel. I watched many of his rhetorically-powerful sermons on television as a teenager, and being that age, had no idea what any of this “pro-Israel” stuff was about. I don’t think anyone who really gets caught up in movements like this genuinely do, either. But it sounded like if I wasn’t pro-Israel, I might as well not even be a Christian.

Hagee and others like him are part of a larger movement called “Christian Zionism,” or “Evangelical Zionism,” and it is the driving force behind American and evangelical support of Israel today.

“Zionism” (or properly, “Political Zionism”) refers to a movement of Jewish people beginning in the late 1800s meant to create their own nation-state. As a minority group who have suffered persecution and military occupation for…well, since the Old Testament!—why not just cut the crap and just create their own country? Because Jewish persecution was pretty bad in the 1800s, especially in Russia. And France, Britain, and Spain all kicked them out, too. (#JewishlivesMatter!)

Zionism: a movement for (originally) the re-establishment and (now) the development and protection of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel. It was established as a political organization in 1897 under Theodor Herzl, and was later led by Chaim Weizmann. (Oxford Languages)

Zionism: Jewish nationalist movement that has had as its goal the creation and support of a Jewish national state in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jews (Hebrew: Eretz Yisraʾel, “the Land of Israel”). Though Zionism originated in eastern and central Europe in the latter part of the 19th century, it is in many ways a continuation of the ancient attachment of the Jews and of the Jewish religion to the historical region of Palestine, where one of the hills of ancient Jerusalem was called Zion. (Brittanica)

The general idea sounds fair enough. But it’s actually problematic if you think about it: in trying to protect one’s own people this way, it tends to be ethnically exclusive (i.e., Jews only) and, well, a bit invasive. Since most of the world was basically already “taken,” how are you going to carve out a space without kicking people out, and without discriminating against those who aren’t Jewish?

As it would turn out, you really can’t. You can create a fake history of an “unoccupied land,” but eventually, you’ll have to drive the bulldozers, pull the trigger, and drop the bombs. For this essay, then, we’re going to call that “Big Problem 1: Ethnic Nationalism.” The problem with creating a country built around a certain people, language, religion, or whatever, is that you risk systematically discriminating and persecuting those who don’t fit in—especially native residents who have been living there for ages. This is why the modern cry for “diversity” and “tolerance” makes sense: we’ve seen where ethnic nationalism goes in the last 500 years (and it ain’t pretty!). So even though one may seem to complement another, it is one thing to try to create a safe-haven for a people, it is another to create an exclusively Jewish nation-state in order to do that. Theodore Herzl himself knew this, as he writes in his personal diary:

We must expropriate gently the private property on the state assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discretely and circumspectly. Let the owners of the immoveable property believe that they are cheating us, selling us things for more than they are worth. But we are not going to sell them anything back. (cited in Morris, Righteous Victims 21-22; Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 4)

It is no surprise that Yusuf Dia al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi, perhaps the premier Islamic and Jewish scholar of that era, wrote to the leader of the Zionist movement: “Palestine is an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, and more gravely, is inhabited by others…Nothing could be more just and equitable [than for] the unhappy Jewish nation [to find refuge elsewhere]” (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 5). Herzl responded by ignoring the problem of kicking the indigenous population out, and employing “a justification that has been a touchstone for colonialists at all times and in all places and that would become a staple argument for the Zionist movement: Jewish immigration would benefit the indigenous people of Palestine. ‘It is their well-being, their individual wealth, which we will increase by bringing in our own'” (Ibid., 6). The Jewish people would bring “their intelligence, their financial acumen and their means of enterprise to the country…”

Most revealingly, the letter addresses a consideration that Yusuf Diya had not even raised. “You see another difficulty, Excellency, in the existence of the non-Jewish population in Palestine. But who would think of sending them away?”…It is clear from this chilling quotation that Herzl grasped the importance of “disappearing” the native population of Palestine in order for Zionism to succeed.

…This condescending attitude toward the intelligence, not to speak of the rights, of the Arab population of Palestine was to be serially repeated but Zionist, British, European and American leaders in the decades that followed, down to the present day.(Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 7).

In other words, the Zionist project was a settler colonialist project from the start.

Many cannot accept the contradiction inherent in the idea that although Zionism undoubtedly succeeded in creating a thriving national entity in Israel, its roots are as a colonial settler project (as are those of other modern countries in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand). Nor can they accept that it would not have succeeded but for the support of the great imperial powers, Britain and later the United States. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War Against Palestine, 14).

All of the arguments for Zionism were thus the same as (to take one of many examples) American colonialists in their justification of violence against the indigenous peoples: “we’re saving you from your own barbarism and savagery; we’ll make you more wealthy; and God has given us the divine blessing to take over your land by force.” One can find this attitude today from the mouths of Ben Shapiro, Donald Trump, Tucker Carlson, and an endless stream of white supremacist figures and organizations. (“Western Civilization rests on colonialism, but colonialism is good, not bad!”)

With this frightening problem on the horizon, Yusuf concluded his letter with prophetic words that still ache the hearts of millions:

In the name of God, let Palestine be left alone. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 5)

Sadly, that would not happen.

Largely based out of Berlin, Germany, the Zionists initially looked at real estate in Russia, Madagascar, Africa, and elsewhere. But, they eventually settled on a target region that seemed natural for them: Palestine.

Palestine and Its People

“Palestine” gets its name from the people who lived there —the “Philistines” (remember that Goliath in the “David and Goliath” story was a Philistine). It’s a small region along the coast of the Mediterranean in the Jerusalem area. It nevertheless maintains impressive variation in geography and climate: desert flats, the sea, rivers, mountains, etc. The “Palestinians” are people who have lived in Palestine for thousands of years. As Nur Masalha writes in the definitive history of Palestine:

“Palestine”…is the conventional name used between 450 BC and 1948 AD to describe a geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River and various adjoining lands…The Palestinians are the indigenous people of Palestine; their local roots are deeply embedded in the soil of Palestine and their autochthonous identity and historical heritage long preceded the emergence of a local Palestinian nascent national movement in the late Ottoman period and the advent of Zionist settler-colonialism before the First World War. (Masalha, Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History, 1)

Philistia is called pelesheth (פְּלֶשֶׁת) in the Hebrew. The LXX [Greek Old Testament] version of the Pentateuch and Joshua called the area the land of the Phylistieim (Φυλιστιείμ). (New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, 358).

Modern military and political propaganda by Zionists contest the use of “Palestine” by using the term “Israel,” hailing back to the Old Testament story. (They also have worked hard to rename historical places, cities, and landmarks to erase indigenous history.) A sharp distinction between “Israelites,” “Canaanites,” and “Phoenicians” is forged as if these were distinct groups with distinct languages and religions. But, despite tremendous variety in the region, this isn’t quite right. For those who are familiar with the Old Testament, it may be interesting to learn that:

The ‘Cana’anites’ are in fact identical to the Phoenicians. The alphabet of the Phoenicians of the coastal regions of Palestine and Lebanon—conventionally known as the proto-Canaanite alphabet—was given to Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, and Hebrew. However, the Old Testament terms ‘Canaanites’ and ‘Israelites’ in Palestine do not necessarily refer to or describe two distinct ethnicities. Niels Peter Lemche, an Old Testament scholar at the University of Copenhagen, whose interests included early Israelites and their relationship with history, the Old Testament and archeology, has suggested that the Old Testament narrative of the ‘Israelites’ and ‘Canaanites’ must be read as ideological constructs of the other (as the non-Jews) rather than as reference to an actual historical ethnic group: ‘The Canaanites [of Palestine] did not know that they were themselves Canaanites. Only when they had so to speak ‘left’ their original home…did they acknowledge that they had been Canaanites’ (Lemche 1999: 152). Literary invention and the fact that the exilic Old Testament authors imaginatively coined the term ‘Canaanites’…does not necessarily indicate that there was a conflict between historical Israelites and Canaanites in Palestine. However, in the modern era (beginning with the late 19th century) European Zionist leaders appropriated the Old Testament narratives as historical accounts and used them instrumentally to justify their settler project and their conflict with the indigenous people of Palestine. (Masahla, Palestine, 57)

Or as one reference work also puts it:

In current scholarship there is broad agreement that the people called Israel, who emerge in Canaan at some point in the early Iron Age (if not earlier), should be considered as one subset of Canaanite culture. For some scholars this means that Israel’s historical origins are literally in Canaan, and the ancestral accounts of an outsider status reflect an ideological stance rather than historical memory. (Dearman, “Canaan, Canaanites,” The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, 535).

This is evident enough in the fact that the Canaanite god “El” was used by Israelites until eventually consolidating into a strict monotheistic worship of “Yahweh.” In other words, Israelite religion (not to be confused with “Judaism,” which comes later) was a product of local social and religious processes that integrated with their “enemies.” We know this because (for example) some of the Pentateuchal tradition is essentially copy and pasted from the 282 laws of King Hammurabi, and because of how we can watch Israelite theism evolve in the Bible itself:

The author of Psalm 82 deposes the older theology, as Israel’s deity is called to assume a new role as judge of all the world. Yet at the same time, Psalm 82, like Deuteronomy 32:8-9, preserves the outlines of the older theology it is rejecting. From the perspective of this older theology, Yahweh did not belong to the top tier of the pantheon. Instead, in early Israel the god of Israel apparently belonged to the second tier of the pantheon; he was not the presider god, but one of his sons. Accordingly, what is at work is not a loss of the second tier of a pantheon headed by Yahweh. Instead, the collapse of the first and second tiers in the early Israelite pantheon likely was caused by an identification of El, the head of this pantheon, with Yahweh, a member of its second tier.

This development would have taken place by the eighth century, since Asherah, having been the consort of El, would have become Yahweh’s consort (mentioned before) only if those two gods were identified by this time. Indeed, it is evidence from the texts such as Isaiah’s vision of Yahweh surrounded by the Seraphim (Isaiah 6), and especially the prophetic vision of the divine council scene in 1 Kings 22:19 that Yahweh assumed the position of presider by this time. (Smith, The Origins of Biblical Monotheism, 48-49)

As we go back further into history, we lose lots of distinctions about people and religion. But we should expect that because human life and culture is like an evolutionary tree with a trunk (earlier) and branches (later). This is why “the idea of ‘one land, two peoples’ rings hollow” (Masahla, Palestine, 44)

Yet, many of you reading have heard things like, “oh these two groups [e.g., Arabs and Jewish people] have been fighting for this plot of land for eternity; no sense trying to get them to get along!” This is untrue and it is irresponsible to repeat this trope. It has been noted by Israeli historians and others that Jewish people, Muslims, and Christians have lived there in harmony doing business with each other for a long time (especially in the 1800s right before things got moving; see Pappe, A History of Modern Palestine). One has to be very careful about these names (and something we won’t have much time to talk about, but also be careful about maps and borders, as well.) Whether we like it or not, and I cannot here elaborate, but it’s a fact: Muslims, Christians, and Jewish people (and their shared “Abrahamic religion”) have gotten along in the same area in all kinds of contexts, for centuries. What causes division are often issues and challenges that transcend these differences, such as economic and political challenges.

Now that isn’t the say everyone always got along throughout history, or that religious contradictions don’t exist.

Mass violence against Jews, akin to the pogroms in Western Europe in the late Middle-Ages and in Eastern Europe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was rare in the Muslim world. But it did occur, often when a Jew who had risen to a senior government position fell from grace, died, or excited the hostility of envious Muslims. In 1066 nearly three thousand Jews were massacred in Granada, Spain. In Fez, Morocco, some six thousand Jews were murdered in 1033, and massacres took place again in 1276 and 1465. There were massacres in Tetuan in Morocoo in 1790; in Mashhad and Barfurush in Persian in 1839 and 1867, respectively; and in Baghdad in 1828. (Morris, Righteous Victims, 10-11)

Yet, Morris still observes that

During the Islamic High Middle Ages, c. A.D. 850-1250, Judaism and the Jews had flourished, and would later designate the period a ‘golden era’ of Jewish history. Jews figured prominently in politics, finance, and the arts and sciences in a number of Islamic kingdoms and empires; one or two served as chamberlains and ministers to kings and princes. Moses Maimonides, a physician to a sultan, emerged as one of the major philosophers of the Middle Ages. (Morris, Righteous Victims, 8)

So, yeah, the “Golden Age” of the Jewish people was (in the view of many) under Islamic rule. That’s important to remember before regurgitating racist, televised nonsense like “Arabs and Jews will never get along” (as if white and European people have historically been so peaceful!).

Before Zionists started buying up property and gradually immigrating to the Middle-East, the religious population of Palestine looked something like this (Morris, Righteous Victims, 4):

Ethnically, over 70% were Arab; another source records that 93% of Palestinians, both Christian and Muslim, spoke Arabic.

In the “First Aliyah” (ascension) from 1881 to 1903, 20-30,000 immigrated to the Palestine region. “And, helped by Western Jewish philanthropists, the movement had managed to purchase, by 1890, about [24,700 acres] of Palestine land, and [50,000] by 1900” (Morris, Righteous Victims, 19). The main organization assembling this activity and sloshing funds was the Jewish Colonization Association (yes, it was actually called that). This immigration and purchasing of land would generally continue indefinitely, and remain a source of power, control, and controversy. By 1939, the Arab population would decline to less than 70% (Morris, Righteous Victims, 122).

I mention all this just so you can get a picture of “how things were” before the major changes that took place around 1948 and following, which is when the Zionists took over and “transferred” (kicked-out) most of the Palestinian residents and restricted them to what is now the The Biggest Prison on Earth, the occupied territories of the Gaza strip and West Bank.

Evangelical/Dispensational Zionism

What, then, is “evangelical Zionism”? What is that thing that people like John Hagee, Pat Robertson (The 700 Club), Jerry Falwell (former Liberty U President) and so many other American “pro-Israel” evangelicals are such a fan of?

In short, evangelical Zionism is American Protestant theology’s justification and reasoning for Zionism. Note that Zionism was primarily a secular movement by Marxists, atheists, and other nationalists. Religious freedom was certainly a factor, but not the only goal. The Zionist movement was “drawn partly from Jewish religious tradition, partly from a Jewish version of the new nationalist ideologies current at the time, and, increasingly, driven by the need to find an answer to reject and persecution in Europe and later the Middle East” (Lewis, The Middle East, 347; cf. Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine and Segev, One Palestine, Complete, regarding Zionism as a response to Western anti-Semitism). So when the Bible and Christian theology got attached to Zionism, this is, well, an interesting development. Why and how did this happen? We’ll look at this briefly later on.

But for now, you should know that (generally) evangelical Zionist reasoning hardly came from orthodox Judaism (i.e., practicing Jews and their traditions), it came largely from dispensationalist fundamentalism. I wrote a whole book on hyper-dispensationalism years ago (ironically, as a raging fundamentalist) and a more recent one on fundamentalism (as a post-fundamentalist), so I have too much to say on these subjects. But to be brief: dispensationalists are European and American fundamentalist Christians (enthusiastically conservative; anti-modern) who forged a specific theology about Israel, the “end times,” and biblical interpretation. Still today, it forms the ideological backbone of evangelical support of Israel even if most pro-Israel Christians are unaware of it.

Dispensationalists emphasize:

- A “literal” reading of the Bible, including the term “Israel” (meaning it always refers to some physical people or nation, never a “spiritual” group like the church).

- A separation between Israel and the church. God has “two programs” for redemption, not one. Israel has its own thing going on, while the church (started in the book of Acts) has a whole different thing going on. It’s always that way. (Some even believe there are eternal destinations for each group.)

- A progressive view of redemptive history broken up into periods (or “dispensations”). For some it’s 6, others 7, others 8. But the main divide that matters for us today comes with the church or with the Apostle Paul (depending on who you ask).

- Escapism: everything’s gonna burn real soon; this world is going to hell in a hand basket, so get your ticket stamped now! Or in preacher Dwight Moody’s own words: “‘I look upon this world as a wrecked vessel. God has given me a lifeboat and said, ‘Moody, save all you can.'”

- All kinds of prophetic deductions from this system, including all the drama of the Left Behind books and films. The book of Revelation signifies all kinds of prophecies about current events. There’s gonna be this “rapture” where true Christians get beamed up and their clothes are “left behind,” then 7 years of nasty tribulation after 1,000 reign of Christ (hence “pretribulational premillennialism”), etc.

This model of theology took off in the mid to late 1800s and early 1900s—incidentally, around the same time Zionism was getting off the ground. Its earliest forms can be found in the writings of Irish preacher John Nelson Darby (1800-1882). Dwight L. Moody’s preaching, C. I. Scofield’s Study Bible, and Dallas Theological Seminary and Moody Bible College systematized it and made it mainstream during the world wars.

That legacy endures. I can still remember seeing all the graphs and charts about the end of the world at Bible camp during my teen years. Or, watching the first Left Behind movie with Kirk Cameron back in the 1990s. This is what “eschatology,” or the study of “last things,” was all about for American evangelical Christians for nearly a century.

Despite all the fanfare and popularity, dispensationalism (like many theologies) has never had much genuine credibility or scholarly recognition. Hardly anyone in academia would defend anything like this today, in or outside a generic Christian perspective. And as a theology, it has problems. The dispensations are a human theological abstraction that are highly debatable (even arbitrary); there’s every reason not to interpret the Bible (and the word “Israel”) literally in thousands of places; there are entire chapters of the New Testament arguing for a unity in God’s plan to transform the world; and it’s just one layer of conjecture and interpretation on top of another, on top of another. Most Christians throughout the last 2,000 years of history never interpreted the book of Revelation like evangelical dispensationalists do (and for good reasons). It remains a remarkably crude and uncritical use of Genesis to apply the promises given to Abraham regarding the land to the modern state of Israel today, and (worse) justify Israel’s war against the Palestinians in 1948 because that is somehow a repeat of Joshua’s conquering of Canaan (something that historians agree probably didn’t even happen, certainly not fully). Nevertheless, denoms like the Evangelical Free Church of America, many Southern Baptists, and others still operate from this framework to this day. Schools/seminaries like Moody, Biola/Talbot, Grace, Liberty, and Dallas continue to perpetuate it, though less and less with each passing decade. (I recently saw a faculty member of an evangelical university display the Star of David on their facebook profile. Given the context of this choice, it was obviously discouraging.)

So why, then, did dispensationalism become popular? Largely because (1) WWI, the Spanish Flu, WWII and other events made the end of the world seem like it was actually happening, so surely the Bible had something to say about it, (2) the Bible was being deconstructed by modern critics and historians, and nobody seemed to care about “biblical authority” like the good ole days. So just as religious-people-on-a-mission-with-their-books get carried away from century to century, everything happening from the 1900s to today can be found somewhere in the Bible or book of Revelation. The Bible needed to come alive and immediately relevant to the church. So literal interpretation and prophecies about the end of the world accomplished that social and political goal pretty well.

In the words of historian George Marsden in Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism:

Dispensationalism…suggests that Christian political efforts were largely futile…Like the early Jerry Fallwell, many fundamentalists tended to view politics primarily as signs of the times that pointed toward the early return of Jesus and set up a political kingdom in the land of Israel. (101, 107)

If Christians couldn’t win the culture and political war, at least they would win when it counted most: saving their souls at the end of the world. (This would completely reverse in the 1980s with the rise of the Moral Majority.)

Lindsey and Carlson’s Late Great Planet Earth (1970) later popularized this end-times fanaticism to epic proportions. Although, nothing seemed to validate evangelical dispensational Zionism more than the creation of the state of “Israel” in 1948. There was all kinds of verses in the Bible about God’s people returning to the land (after having been exiled in 586-7BCE), and these could now be retro-fitted for a future date (aka 1948). But we’ll get to 1948 in just a moment. We first have to discuss what’s wrong with this whole orientation from a theological and biblical-studies perspective…

The Biblical-Theological Problems With Evangelical Zionism

In college I was privileged to have taken an upper-level interdisciplinary history course by a great professor entitled “A History of the Muslim World.” We read from Goldschmidt’s A Concise History of the Middle East 8th ed (read my original notes of it here), some of the work by Bernard Lewis (including his 1990 classic essay, “The Roots of Muslim Rage”), John Esposito’s Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam, and, for my theology major, most important of all, a book by Wheaton New Testament Professor Gary Burge entitled Whose Land? Whose Promise?:What Christians Are Not Being Told about Israel and the Palestinians (read my original notes of it here.

I wasn’t actually a fanatical defender of Israel at any point in my life. But dispensational Zionism was the only ideology I was familiar with, and as I already iterated, it was part and parcel of my whole religious experience. For me, to be Christian was (among other things) to be “pro-Israel.” But by the end of this course, it was clear that I had been severely misinformed, and that I desperately needed to revamp my entire understanding of eschatology, political theology and Middle-Eastern history. (This was, I would add as an aside, a testament to the effectiveness of an authentic liberal arts education.)

Burge’s contention was relatively simple. Christian Zionists argued that “Israel” (the Jewish people) had an unconditional right to “take back the holy lands” like Joshua conquering Canaan in the Old Testament. But even if this Zionist framework was true, even if we could rashly reduplicate the story of Joshua and the Canaanites from the ancient world and project it onto the Zionists and Palestinian Arabs of the 20th century, there’s a big problem: the same Hebrew Bible that promised a “promised land” to “Israel” also erected all kinds of conditions for taking it and living on it. As Burge asserts, “If Israel makes a Biblical claim to the Holy land, then Israel must adhere to biblical standards of national righteousness” (p. 31).

These conditions are present in a variety of ways:

- “Do not [x y z…] otherwise the land will vomit you out for defiling it, as it vomited out the nation that was before you.” (Lev. 18:24-30; 20:22-26)

- “To break the law is to lose the land.” (Burge, 74; see Deut. 4:25-27. 50; 8:17-19 – “Do not say to yourself ‘My power and the might of my own hand have gotten me this wealth.”

The land is also never anyone’s absolute possession, but God’s alone (even for the Israelites!):

- “For the land is mine; with me you are but aliens and tenants.” (Lev. 25:23) p. 75

- “The divisions of the land were God’s decision, not that of the people of Israel” (Burge) (Ex. 28:30)

- The Jubilee made “long-term investments in which wealthy people would develop huge estates “impossible.” (p. 76)

- Harvests were even owned by God.

- “When you enter the land that I am giving you, the land shall observe a Sabbath for the Lord.” (Lev. 25:2)

The same goes for the controversial commodity of that area: water.

- God owns the water (Job 5:10).

- “The Lord will open to you his good treasury in the heavens, to give the rain of your land in its season and to bless all the work of your hands and shall lend to many nations, but you shall not borrow.” Deut. 28:12

- Withholding water was God’s way of punishing Israel (Amos 4:7, Joel 1:10-12)

- “The most famous of these pronouncements is perhaps Elijah’s promise that neither rain nor dew would fall on Israel until the land was righteous (I Kings 17:1).” (p. 78)

The Zionist soldiers that established the modern state of Israel broke virtually all of those conditions from the 1940s to the present day. Yahweh would say, then, “Get out!” But evangelical (and other) Zionists ignore all of this and continue to assert an “unconditional right over the land.”

This points to the fact that contemporary Christian support of Israel is not even theological or “biblical” at all, but shaped by contemporary politics and protection of capitalist wealth. (Of course, we saw some of these connections more recently when President Donald Trump declared Jerusalem the capital of Israel largely to consolidate evangelical support; and not unironically, a leading defense attorney at Trump’s impeachment trial was Alan Dershowitz, author of The Case for Israel, not to be confused with John Hagee’s In Defense of Israel. Though, they’re both probably of the same quality and value.)

Furthermore, Burge shows in his other book Jesus and the Land: The New Testament Challenge to “Holy Land” Theology that Jesus was anything but an ethnic nationalist. He did not try to forcefully (or even peacefully) “transfer” the Romans, or anyone else, from the “holy lands” to establish a Jewish state. In fact, it was just the opposite. Jesus was radically inclusive regarding who is part of new “Israel,” whether it comes to the Canaanite woman (Matt 15; historically Israel’s enemies), Samaritans (considered ethnic “half-breeds” and religious heretics), Roman centurions (Luke 7; Matt 8; pagan military colonizers), or desert odd-balls like John the Baptist (probably an Essene who hung out around Qumran, the site of the Dead Sea Scrolls). Jesus undoubtedly cared about the Roman occupation and the exile of Israel (which goes back to the 587BCE conquering of Jerusalem), but…he didn’t exactly pull a Joshua and go on a killing spree, even if that’s what many Second-Temple Jews and even some of his disciples were prepared to do (like Simon “the Zealot”).

The Apostle Paul, like anyone else who encountered Jesus, was sort of blown away by this whole “Kingdom” project. It was a fulfillment of ancient promises (like those given to Abraham that his descendants shall be more “numerous than the stars in the sky”), but it was also beyond those hopes, or a least a new spin on them. Jesus’ “Kingdom of God” was frankly (to mix some terms) a disturbingly socially-progressive world-and-life view, “counter-cultural” for a lack of better words. Paul elaborates his Christ-vision for the church in his letter to the Romans, explaining this Gentile inclusion with regard to those Abrahamic promises (chapter 3-5), and later on where “Israel” is like a historical “root” or “trunk” of a tree (chapters 9-11). With the coming of Christ, branches were cut away to make room for non-Jewish people, resulting in one tree comprised of a variety of peoples. Furthermore, the sign of this “New Covenant” was no longer male-only Jewish circumcision (a bloody act of pain and coercion), but water baptism for all (a cleansing, voluntary, refreshing act of peace and renewal). As a symbol, the inclusive nature of this new era was clear.

Paul (or whoever of Paul’s fans wrote it) provides another illustration in Ephesians 2, where the metaphor here is a “wall of hostility” that’s broken down:

11 So remember that once you were Gentiles by physical descent, who were called “uncircumcised” by Jews who are physically circumcised. 12 At that time you were without Christ. You were aliens rather than citizens of Israel, and strangers to the covenants of God’s promise. In this world you had no hope and no God. 13 But now, thanks to Christ Jesus, you who once were so far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ.14 Christ is our peace. He made both Jews and Gentiles into one group. With his body, he broke down the barrier of hatred that divided us. 15 He canceled the detailed rules of the Law so that he could create one new person out of the two groups, making peace. (Eph 2:11–15, CEB)

Earlier in his ministry he made the same point:

You are all God’s children through faith in Christ Jesus. 27 All of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. 28 There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. 29 Now if you belong to Christ, then indeed you are Abraham’s descendants, heirs according to the promise. (Ga 3:26–29, CEB)

Because this seemed to threaten Jewish identity (culture, religion, etc.), Paul and other Christ-followers naturally found themselves in conflict with various Jewish groups, despite still being Jewish (…sort of). Paul himself found this inclusion of non-Judeans in the grand scheme of things to be incomprehensible. He calls it a profound “mystery” in various places (Rom 11:25; 16:25-26; Eph 3:3-7). And that grand mystery, which has been revealed with the Christ-event, is that the Gentiles would be coheirs and parts of the same body, and that they would share with the Jews in the promises of God in Christ Jesus through the gospel” (Eph 3:6).

Paul was probably as surprised as Jesus’ disciples when Jesus proclaimed:

And don’t even think about saying to yourselves, ‘Abraham is our father.’ I tell you that God is able to raise up Abraham’s children from these stones. (Matthew 3:9, CEB)

Ok then!

This radical, transformative inclusivity, centered around love, forgiveness, and community, is one of the main reasons for how “Christianity” became distinct from Judaism and forged its own religion. In fact, it was so central to this new “Christian” identity that when Peter started separating himself from non-Jews at the lunch table (like the old days of being “under the law”), Paul “rebuked him to his face” (Gal. 2:11)! This was actually (as N. T. Wright argues) the origins of the “doctrine of justification.” The question was about circumcision and “who one is allowed to eat with”—both of which are badges of “who is in” or “justified” (What Saint Paul Really Said, 141).

But this inclusivity is also one of the biggest reasons no Christian today should entertain the kind of ethnic exclusivity (ok, let’s just call it what it frequently amounts to: racism) inherent to both contemporary Zionism and evangelical Zionism. To continue to erect a wall between the Jewish people (and their modern secular state of Israel) and the Christian community—as evangelical “supporters of Israel” do today—is to reject the New Covenant in Christ, the “good news” that all of us can have a seat at the table, eat together and create a new world without walls of hostility.

So to my fellow Christians who may be reading this, I conclude as the Apostle does:

Conduct yourselves with all humility, gentleness, and patience. Accept each other with love, 3 and make an effort to preserve the unity of the Spirit with the peace that ties you together. 4 You are one body and one spirit, just as God also called you in one hope. 5 There is one Lord, one faith, one baptism, 6 and one God and Father of all, who is over all, through all, and in all. (Ephesians 4:2-6)

Interlude

WWI and “Big Problem 2”

Most of that “History of the Muslim World” course focused on Islamic and Middle-Eastern history, and it is there that we encounter “Big Problem 2: British Morons Screw Over Everyone.”

If you recall, Big Problem 1 was Ethnic Nationalism. The Zionist program was destined to create problems because of its strict goals. Creating a safe haven for Jewish people and creating an ethnically-exclusive Jewish state are different things. The Zionists were a product of their time and laser-focused in achieving their goal (a goal continues to be recklessly pursued). But a second problem was brewing around the same time Zionism was getting off the ground.

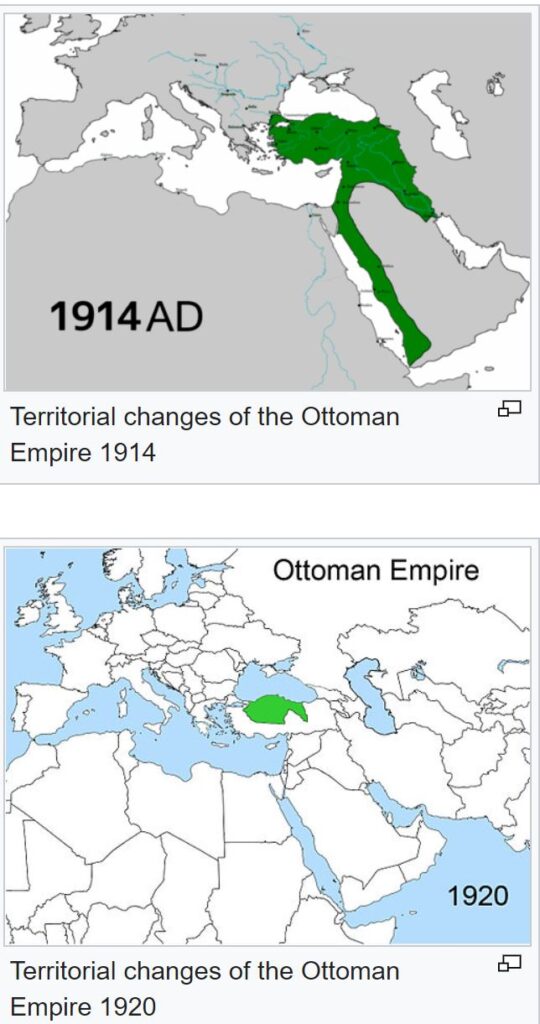

Palestine (and much larger chunks of the Middle-East) was controlled by the Ottoman Empire for an impressive 400 years (1517-1918). This long and proud Muslim rule ended when the Ottoman empire (along with Germany and Austro-Hungry Empire) lost World War I (see map below).

What happened during this short period from WWI to the beginning of WWII would plant the seeds for the notorious Palestinian-Israeli conflict that endures to this day.

First, we must note that the Ottoman Empire was saturated in its own nationalist ambitions. (It seems like almost every country on the planet was suffering from the disease of authoritarian nationalism in this period). The Empire was large and diverse enough that Arabs wanted to reform or divide to create their own independent Arabic state, similar to how the Zionists wanted their own Jewish state. The Empire was also undergoing centralizing reforms that alienated Arabs. This caused all kinds of factional movements, like the Ottoman Decentralization Party (1912), Al-Fatat (youth; demanded equal rights for Arabs, 1913), and Al-Ahd (Covenant; a “secret society of Arab officers in the Ottoman Army” who tried to make it a dual-monarchy – similar to Austria-Hungary government at the time).

Second, the British shrewdly leveraged these internal problems for their own advantage in winning the War. This included the “Husayn-McMahon Correspondence” (1915-1916), where Britain’s high commissioner Sir Henry McMahon wrote to the Sharif of Mecca in order to persuade him to revolt and tear down the Ottoman Empire from the inside.

Britain pledged that, if Husayn proclaimed an Arab revolt against Ottoman rule, it would provide military and financial aid during the war and would then help to create independent Arab governments in the Arabian Peninsula and most parts of the Fertile Crescent…

The Arabs argue, therefore, that Britain promised Palestine to them. (Concise History, 211)

So that was the deal. The Brits said, “Hey Ottoman dissenters, you help us take down your empire and we’ll give you what you ultimately want.”

So the day came: the Arabs revolted June 6, 1916 as planned. And soon enough, the Ottoman Empire collapsed, as planned.

However, after WWI ended and the allied forces eventually took over Palestine, the British and the Zionists denied that McMahon promised Palestine to the Arabs. In fact, France, Russia, and Britain had already met behind closed doors to exclude the Arabs in what eventually became the “Sykes-Picot Agreement”, dividing up land according to their own plans. The French would get North Syria, including the central Islamic cities of Aleppo and Damascus, and Britain would rule over lower Iraq.

But then came a second and more serious stab in the back. On November 2, 1917, the British announced their plans to help the Zionists establish an independent Jewish state in Palestine. This was the infamous “Balfour Declaration” named after “Bloody Balfour” (former British chief secretary of Ireland and author of the 1905 Aliens Act that prevented Jewish people from escaping British pogroms; yes, ironic!).The Declaration was a one-sentence decision made known in the form of the following letter:

Foreign Office

November 2nd, 1917Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you. on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours,

Arthur James Balfour

This was obviously a crappy deal for those Arabs living in Palestine, because they made up 9/10 of the population and the Declaration didn’t make any clear provisions for their protection (especially political and national protection).

For the inhabitants of Palestine, whose future it ultimately decided, Balfour’s careful, calibrated prose was in effect a gun pointed directly at their heads, a declaration of war by the British Empire on the indigenous population. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 25).

The British occupied Jerusalem a month later and banned publication of the declaration. “Indeed, the British authorities did not allow newspapers to reappear in Palestine for nearly two years” (Khalidi, 26).

At first, some prominent Arabs were more optimistic about the possibilities of both sides getting what they want. This is demonstrated in the early 1919 correspondence between Emir Faysal and Chaim Weizmann (Zionist leader), and between Faysal and Felix Frankfurter, where Faysal opens: “We feel that the Arabs and the Jews are cousins in race, having suffered similar oppressions at the hands of powers stronger than themselves, and by a happy coincidence have been able to take the first step towards the attainment of their national ideals together” (Laqueur and Rubin, The Israel Arab Reader, 17-19). This is significant because Faysal was not only the son of the Sharif of Mecca and future King of Iraq, but the leader of a government in Damascus that “Palestinians hoped their country would become the southern part of this nascent state” (Khalidi, 33). Unfortunately, France ended those hopes by occupying Syria according to the Sykes-Picot agreement in July 1920.

In the post-war negotiations, the King-Crane Commission of August 1919 (appointed by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson) realized that the Zionist proposal was the most controversial and heading for disaster, so they decided to scale it back. It would “limit Jewish immigration into Palestine, and end any plans to turn the country into a Jewish national home” (Concise History, 217). Winston Churchill in “The Churchhill White Paper” (June, 1922) also dialed back Zionism and said he wouldn’t give preference to Jews over Arabs.

But this was all for nothing. The official “British Mandate” of the League of Nations—what actually became the law of the land, “specifically charged Britain with carrying out the Balfour Declaration” (280) just a month later. In fact, to almost everyone’s surprise, it expanded the Declaration in its Articles.

In the third paragraph of the Mandate’s preamble, the Jewish people and only the Jewish people, are described as having a historic connection to Palestine. In the eyes of the drafters, the entire two-thousand-year old built environment of the country with its villages, shrines, castles, mosques, churches, and monuments dating to the Ottoman, Mameluke, Ayyubid, Crusader, Abbasid, Umayyad, Byzantine, and earlier periods belonged to no people at all, or only to amorphous religious groups…The surest way to eradicate a people’s right to their land is to deny their historical connection to it. (Khalidi, 34)

Thus, “Meeting in San Remo in 1920, British and French representatives agreed to divide the Middle East mandates: Syria (w/Lebanon) to France, and Iraq and Palestine (and Jordan) to Britain” (A Concise History, 218).

What about all of the contradictory statements the British had made? What about any kind of protection for Palestine’s inhabitants? Bloody Balfour was clear: “For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country…Whatever deference should be paid to the views of those who live there, the Powers in their selection of a mandatory do not propose, as I understand the matter, to consult them” (cited in Khalidi, 38).

But the Palestinians weren’t going to just roll over and watch themselves get displaced. So Muslim and Christian organizations formed their own Palestine Arab Congresses from 1919-1928. “These congresses put forward a consistent series of demands focused on independence for Arab Palestine, rejection of the Balfour Declaration, support for majority rule, and ending unlimited Jewish immigration and land purchases….[But] it was a dialog to the deaf” (Khalidi, 31). Indeed, Zionist propaganda continued, asserting that “under no circumstance should [Zionists] talk as though the Zionist program required the expulsion of the Arabs, because that would cause the Jews to lose the world’s sympathy” (cited in Segev, One Palestine, Complete, 404). This strategy of leveraging national sympathies would be amplified when the world discovered the horrors that had happened in Auschwitz.

Tensions also naturally rose at the religious and geographical center of it all: the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The Temple Mount has been built, destroyed, and rebuilt so many times I won’t bother summarizing that history. But just know that the temple mount remains a holy site for Christians, Muslims, and Jews all at the same time. Since most reading this are probably familiar with Judaism and Christianity, I won’t explain its significance for them. I’ll note that it is holy to Muslims because of the “Dome of the Rock,” one of the earliest Muslim structures, where Muhammad himself is said to have journeyed in the night sky to speak with Moses and Jesus. The Dome is not a mosque. But there is a mosque next door on the Mount that the Crusader’s named “Solomon’s Temple.” It was the mosque that was invaded by Israeli police this May and got all the bombings and rocket-fire going.

Because this single location is sacred to so many, it has often been difficult at keeping peace. So, in 1928, Jewish worshipers erected a screen structure at the sacred Western (“Wailing”) Wall that separated women and men. Before that, both men and women worshipped together. The Muslim sheikhs objected to this move, seeing it as iconic, Zionist intrusion on sacred space and a middle finger to religious tradition. British policeman took it down, to which Jewish worshippers then attacked the policeman, followed by public marches of “this wall is ours”, etc. Soon enough, violence breaks out, and Arabs are committing senseless atrocities against various Jewish people, though both suffered casualties.

(Side note: That same year the Muslim Brotherhood was established in Egypt as a activist and militant response to Islamic decline and Westernization in the Middle-East.)

By 1930-33, Hitler’s regime sent masses of Jewish refugees flocking into the area, compounding the tension. Europe was already full; Canada and the U.S. (shamefully) refused to let Jewish immigrants in. The British started to scramble as things slid out of control, and jerked around both Arab and Zionist parties once again. Sir John Simpson published a report about Jewish immigration in October of 1930. As a result, Lord Passfield in the “Passfield White Paper” limited Jewish immigration and criticized the negative effects of the Zionist immigration program on the native Arab population. But then, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, James MacDonald, wrote a letter to Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann nullifying all these rules and jumping on board with the Zionists. Once again: the British say one thing, only to take it back. Besides all this, the seven Arab congresses were over and had gotten nowhere, and now this!

The Palestine Arab Executive issued a Declaration (cited in Morris, Righteous Victims):

We must give up the idea of relying on the British Government to safeguard our national and economic existence…Let us seek help from ourselves and the Arab and Islamic World…Mr. MacDonald’s new document has destroyed the last vestige of respect every Arab had cherished towards the British Government.

Anti-Zionist and anti-British violence escalates again. “Initially, the Arabs restricted themselves to arson in the towns and sniping, crop-burning, and tree destruction in the country side. Then came attacks on Jewish traffic and farmers in the fields….In the towns the Arabs began throwing bombs and grenades at Jewish homes and cars” (Morris, Righteous Victims, 137). The British sent in tens of thousands of troops to calm the storm.

Meanwhile (to complicate matters), oil concessions in the Middle-East transform the whole economy. For example, in 1933, Ibn Sa’ud gives Americans a 60-yr concession to search for oil in Hasa. Although the Russians were getting oil from the Aspheron peninsula as early as the 1860s, the British, Dutch, American and French were now able to exploit the fields and bring massive amounts of oil to the global market (Lewis, The Middle East, 352). Future conflict in the Middle East would almost always involve control over oil refineries and pipelines.

By 1936, Arab-Zionist tension reached critical mass. Jerusalem’s chief mufti and Arab nationalist, Hajj Amin al-Husayni, formed a committee representing Muslim and Christian factions that called for a six month general strike. This was the beginning of the “Arab Revolt” (1936-39), where various Arab groups attempt to throw off both British rule and Jewish incursion. They also begin to seek desperate alliances with fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. The newly-formed Arab Higher Committee told its militias, “We stand now in a period of hope and expectation. If the Royal Commission comes and judges equitably and gives us all our rights, well and good. If not, the field of battle lies before us…We request…self control and armistice until a new notice” (cited in Morris, Righteous Victims, 135).

Since the British controlled the whole area and the whole Middle-East was about to erupt in war, it was time for another intervention. Sir Lord Peel summoned the Palestine Royal Commission (1936-7), which proposed the only solution they could think of: splice and dice the land into partitions for each group. But since this meant that 200,000 Arabs would simply be expelled (or in colonialist language, “transferred”) and the British would still rule, the Arab High Commission rejected it unanimously, and proposed an independent Arab state instead, “with protection of all legitimate Jewish and other minority rights and safeguarding of reasonable British interests,” and demanded that Jewish immigration and purchasing of land stop. After all, the British colonialist overlords already screwed them over before WWI was even won, and then again after the war. So how can they be trusted now—now that they have all the power?

The Zionists, on the other hand, were uncertain about the Peel Commission’s plan, but saw it as a stepping stone to taking over all of Palestine. Ben Gurion’s ethnical nationalism was particularly forceful, as this 1937 quote from his personal diary illustrated: “We will expel the Arabs and take their place.” There was also a saying in Jewish communities at this time: ein breira (“there is no choice”; a sort of fatalistic saying meaning that “Yishuv [the Jewish community in Palestine] would have to live by the sword,” Morris, Righteous Victims, 135). In any case, “Ben Gurion understood that…if the British did not exercise force [to expel the Arabs], the Jews would have to do the job” (Morris, Righteous Victims, 142).

At this point, the British effectively cut support for any kind of Palestinian state and severed Palestinians’ political and national rights, and any kind of system for obtaining help from the outside world.

Unlike the Jewish Agency, which had been granted vital arms of governance by the League of Nations Mandate, the Palestinians had no foreign ministry, no diplomats, nor any other government department, let alone a centrally organized military force. They had neither the capacity to raise the necessary funding, nor international assent to creating state institutions. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War, 62).

Worse, Jewish terrorism really took off—and in deadly new ways:

…for the first time, massive bombs were placed in crowded Arab centers, and dozens of people were indiscriminately murdered and maimed—for the first time more or less matching the numbers of Jews murdered in the Arab pogroms and rioting of 1929 and 1936. This ‘innovation’ soon found Arab imitators and became something of a “tradition”…

The Irgun bombs of 1937-38 sowed terror in the Arab populations and substantially increased its casualties. Until 1937 almost all of these had been caused by British security forces (including British-directed Jewish supernumeraries) and were mostly among the actual rebels, but from now on, a substantial portion would be caused by Jews and suffered by random victims. (Morris, Righteous Victims, 147)

Unfortunately, the Royal Commission’s solution was a no go. In fact, it just blew the lid off the whole volcano. Mass violence erupts. People get deported. Arab militants conquer territories while Jewish and British agents (the Special Night Squads) start bombing Arab markets as they protect the Iraq Petroleum Company pipeline. The Brits declare martial law and send in 20,000 strong to quell the surge. By the time WWII begins, there’s 1 British soldier for every 4 Palestinians (Khalidi, 44).

The crackdown was ruthless. The Brits put to death any Palestinian who possessed a single round of ammunition, thousands were detained and imprisoned without trial, dozens were sent to British concentration camps, and hundreds deported into exile around the world (Khalidi, 45). But, you guessed it: instead of ending the revolt, this crackdown only intensified resistance. Thousands of more troops were sent in as the blood spills over. By 1938, the Palestinians themselves had turned their guns on each other because of disagreements over the Peel Commission and whether or not to compromise.

This isn’t exactly what the British needed in order to fend off the Nazis in what would become World War II. So in a last-ditch effort, they called the 1939 London Commission in February which was chaired by the British Prime Minister himself, Neville Chamberlain. By this point, the British were talking about ending the Mandate entirely and leaving Palestine. (Colonialist fail.)

The London Commission invited leaders from the kingdoms of Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, and the Emirate of Transjordan. The Zionists were led by Chaim Wiezmann who chaired the World Zionist Organization (though he was a puppet under the control of Ben Gurion, leader of the Jewish Agency). The Brits’ major proposal was a unified government representing the demographics of the population…and also, of course, maintaining British power:

- 2 Seats Christians

- 2 Seats for Jews

- 8 Seats for Arabs

- 10 Seats for the British Officials

For obvious reasons, nobody liked this plan except the British. And after some 5+ weeks of negotiations, predictably, nothing could be resolved. So, once again, the Brits decided on their own what would be “the law of the land” in the “White Paper”:

- Forget the partition plan of the Peel Commission; the Jewish people would have some kind of national home within 10 years.

- Yet, Jewish immigration was limited to 75,000 people per year, and anything more was to be determined by the Arab majority.

- The Jewish people were restricted from buying Arab land in all but 5% of the Mandate.

Some Arab groups rejected while some were more open to it, since it at least didn’t give the Zionists total control over the land. With the risk of losing everything, compromise didn’t seem all that bad for some. However, most Palestinians knew the British couldn’t be trusted to fulfill their promises anyway, so why bother with these games?

The Zionists, however, despite getting approval for their national home, rejected the White Paper entirely and called for a general strike. Then, in September, the Nazis invade Poland and World War II begins. All hell breaks loose.

WWII and the Not-So-Glorious Creation of Modern Israel

People are fleeing everywhere with nowhere to go as the Nazis conquer one populated region after another. Jewish people in particular are forced into the chaos of Palestine because of the holocaust, giving the Arabs a bigger headache. In fact, for the first time, the Jewish economy is larger than the Arab economy. “Palestinians now saw themselves inexorably turning into strangers in their own land” (Khalidi, 41).

The British needed all the military support they they could find and the Middle-East was geographically strategic (that’s largely why they occupied the area in the first place). But in a wise choice, most Arab countries remained relatively neutral during the war, though leaning towards the Axis powers because they were anti-Western (anti-British, anti-American). The Arabs had reached out to support Germany as early as 1933. The Nazis were unusually anti-Jewish, after all, which obviously aligned with Palestinian defenses from Jewish incursion. But on the other hand, the Nazis kept sending Jewish people to Palestine, which is precisely what the Palestinians didn’t want.

Support for the Axis was in part based on ideology, but owed much more to the old and still valid principle of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” The main attraction of the Axis was that it was the implacable enemy of the West [i.e. the British]…In any event, both sides of the Second World War disappointed their supporters in the Middle East, and were disappointed by them. Both sides managed to mobilize some military help…The Germans disappointed their Arab followers and suitors. (Lewis, The Middle East, 350)

The Zionists, however, would support the Allied powers. In Ben Gurion’s words, “We must assist the British in the war as if there was no White Paper and we must resist the White Paper as if there was no war.” This was a chance to cement British support for the Zionist project, gain further allied support from the West, and also mobilize the necessary military forces to overthrow the British and conquer any resisting Palestinians/Arabs when the war was over. In short, WWII brought the necessary chaos and comparative advantage necessary to achieve the Zionists’ radical goals.

Meanwhile, the world began to hear about the horrors of the Jewish holocaust under Nazi Germany, for which the Zionists begin to gather significant American and international support. After all, kicking out a million residents in Palestine to establish a safe-haven seems like nothing compared to 6 million people getting gassed, burned, and tortured by the Nazis. (In some sense, it isn’t, though this comparison is rather needless to make given the needless achievement of Zionist goals for a peaceful Jewish community.) Christians also had reasons to be anti-Arab that go back to the Arab massacre of Christian communities in the 1850s in the region (Aleppo, Nablus, Damascus, Lebanon). It’s a long story. But,

Among the long-term consequences of these bitter internecine conflicts were the emergence of a Christian-dominated Lebanon in the 1920s-40s and the deep fissure between Christian and Muslim Palestinian Arabs as they confronted the Zionist influx after WWI. (Morris, Righteous Victims, 8)

By 1942, American Zionists adopted the Biltmore Program, which called on Britain to rescind the White Paper and make Palestine a Jewish state.

The War ends in 1945, and in 1947, the British finally turn over their failed colony experiment to the UN. So in November 29, 1947, the UN (primarily under the power of the U.S. and U.S.S.R.) proposes a new Partition plan that passes by 33/13 vote.

But with the Zionist goal so close at hand, with a formidable and consolidated military force, and with British forces finally starting to pull out, it was time to go while the going was good. In July of 1946, the Zionists go for the jugular and bomb the British Headquarters in Jerusalem (July 1946), killing 91 people in the King David Hotel.

Now came the big, dirty, and bloody project that was decades in preparation: purging Palestine of its non-Jewish inhabitants.

Seeing this as an opportunity to move a population, Israel then closed its borders, refusing reentry to most of the refugees following the war. Soon hundreds of Arab villages were destroyed (over 350 of them), making any return an impossibility. (Burge, Whose Land?, 39)

This was not simply a random act of opportunism, it was a carefully crafted strategy.

Plan Dalet involved the conquest and depopulation in April and the first half of May of the two largest Arab urban centers, Jaffa and Haifa, and of the Arab neighborhoods of West Jerusalem, as well as of scores of Arab cities, towns, and villages, including Tiberias on April 18, Haifa on April 23, Safad on May 10, and Beisan on May 11. Thus, the ethnic cleansing of Palestine began well before the state of Israel was proclaimed on May 15, 1948. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War, 72)

The Deir Yassin massacre on April 9 was particularly brutal, where around 250 people were slaughtered. Some other villagers “were driven through Jerusalem in a ‘victory parade’ before being taken back to the village and shot” (Burge, Whose Land?, 39-40).

In order to guarantee that the Arabs would not return, the villages were generally destroyed and their village wells poisoned, generally with typhus and dysentery bacteria…Today the Israeli authority, Mekorot, regularly checks wells in rural areas since, according to many technicians, soldiers poisoned virtually every Arab well they captured. (Burge, Whose Land?, 40)

The situation wasn’t much better in the large cities.

Jaffa was besieged and ceaselessly bombarded with mortars and harassed by snipers. Once finally overrun by Zionist forces during the first weeks of May, it was systematically emptied of most of its sixty-thousand Arab residents. Although Jaffa was meant to be part of the stillborn Arab state designated by the 1947 Partition Plan, no international actor attempted to stop this major violation of the UN resolution.

Subjected to similar bombardments and attacks on poorly defended civilian neighborhoods, the sixty thousand Palestinian inhabitants of Haifa, the thirty thousand living in West Jerusalem, the twelve thousand in Safad, six thousand in Beisan, and 5,500 in Tiberias suffered the same fate. Most of the Palestine’s Arab urban populations thus became refugees and lost their homes and livelihoods. (Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War, 73)

On May 14, 1948, the Jewish soldiers declared “independence” for the state of “Israel.” Although the state department was utterly torn, within 11 minutes, American President Truman formally recognized the state of Israel. The rest of the world was stunned.

The Arabs declared war. But it was of no use. With superior forces and skill left over from WWII, Israel won decisively and redrew the map, “acquiring more land than was even offered in the U.N. partition” (Burge, Whose Land?, 39). Jordan maintained control over the West Bank and East half of Jerusalem.

During this second, “post-war” phase, another 400,000 Palestinians were expelled. The demolition of Arab houses continues to this day.

Since 1967, Israel has worked to change the ethnic character of Jerusalem. Government officials have discussed and implemented racial quotas in order to ensure a large Jewish majority. As the population density of Palestinians in the city increases, Arabs face impossible decisions. If they reside outside the city limits, they will lose their “residency” card to return for employment. If they try to build on family-owned land, they are not given building permits. From 1967 to 1999, only 2,950 permits were given to Arabs—and so they construction takes place in Jerusalem as well, but in this case the land is often not owned by the builder. Palestinians are responsible for about 20% of illegal construction, yet 60% of demolitions are carried out against them. From 1987 to 2000, Israel demolished 284 Arab homes in East Jerusalem, leaving many people homeless. When the second uprising was at its height (2000-2003) Israel destroyed about 300 homes. From 2004 to 2012 they destroyed 412 homes, leaving 1,636 people homeless. (Burge, Whose Land?, 2013:131)

Conclusion

1948 marked perhaps the most significant turning point in this history:

- Israel did not fight a “defensive war for independence” (a popular myth), it eradicated civilian populations, violated international law, and took the place of their former master (Britain) as the de facto colonizer, achieving superior national, political, and military status over the land. (Despite what you’ve heard, the flu virus and car crashes are a bigger safety threat to Israel and Jewish citizens than rockets coming out of the Gaza strip.)

- Unlike the British, Israel went further in a campaign of ethnic cleansing—overtly racist violence against indigenous peoples with the goal of total replacement, which is maintained to the present day.

- Israel faces virtually no resistance by any political body in this campaign of colonialism and cleansing, and maintains a steady supply of military funding from the United States at over $3.5 billion every single year. As we have seen this month (May 2020), the U.S. cannot even admit that Palestinian children have been killed by Israel, nor admit in public that it is wrong for Israel to commit war crimes. President Biden blocked a U.N. resolution four times and even tried to send Israel $735,000,000 in bombs and arms. (Days later he flipped to then offer the Palestinians millions in aid that was previously cut off by Trump; some politicians called this out, like Jewish Senator Bernie Sanders). So there you have it: Americans both provide Israel bombs to destroy the Palestinians, and the medical supplies and funds to pick up the pieces in Palestine.

Since these pivotal events in 1948, Palestinians and supporting Muslim groups continued their resistance, establishing the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) and other organizations. As a people trapped in an apartheid state, many have used and continue to use all means possible—negotiations, political pressure, protests, violence and terrorism—as well as all ideological means possible (e.g., religious fundamentalism, jihadism, appeals to UN principles, human rights and social justice, etc.) to achieve liberation.

Post-Script: An (Un)Holy Land Tour

Given my evangelical background, it was not surprising that I landed a faculty position at a Zionist, evangelical school (John Witherspoon College) early in my career. JWC held holy-land tours to Israel every two years, even though we had less than 50 students. It was top-priority, because, well, Israel is “God’s people” and (equating anti-Semitism for anti-Zionism) “they’re under constant attack.”

But by the time of that 2013 tour—which spanned across not only Israel but also Jordan—I was thoroughly disgusted by evangelical Zionism. It made no theological sense and it was ethically absurd to try and justify. The lemon festival of this tour had moments of lemonade for Jessica and I (like being in a boat during a storm on the Sea of Galilee, walking in a stream where David may have drew his smooth stone from, and escaping our hotel in Jordan to have tea with a Muslim family off the beaten path). Nevertheless, spending 12 days on a bus with Southern Baptists fundamentalists obsessed with “the Jews” was downright nauseating.

It was, indeed, an interesting cultural experience to witness the industry of Zionism—the shops, the commerce, and the ideologies and discourses. “I can’t believe abortion rates are so high here. I mean, it’s Israel! God’s people! Unthinkable!” I remember hearing at one point. Combined with high rates of atheism, many tourists were shocked to learn that Jews were not white American evangelicals (like they apparently had been imagining all these years). Christian churches were hard to find, though they existed.

But most of the time, their eyes were diverted—and we certainly didn’t visit any Christian churches in Gaza. We visited the West Bank and Bethlehem, but only to talk with Christians or other evangelicals, not Arab Palestinians. All things Arab and Muslim were, for the most part, kept at a distance and out of view—just like the Custer State Park Visitor’s Center mentions nothing about the Native Americans who lived there for thousands of years. The white supremacist and colonialist myth of a “land without a people” continues all over the globe.

10 hours a day. Endless locations. Top to bottom, from Jerusalem to the Golan Heights to Jordan to the Dead Sea to Qumran to Beersheva to Caesarea by the Sea. Nonstop lectures by two knowledgeable tour guides. And? We learned absolutely nothing about the Palestinians or Gaza. No one on that tour bus had any idea that what they were witnessing was a successful century of settler colonialism, genocide, and unimaginable suffering.

We knew this would happen. We knew we would only see things we were supposed to see. It’s why we flew in early and flew out late so we could at least try and see things from a different perspective.

On the first couple days of the trip we drove to Eilat on the Red Sea, a tourist location for all kinds of people (including Russians apparently). Outside of town, we walked among 3,000 year old copper mines by the Egyptians and visited a wildlife refuge (and avoided being attacked by hungry Ostriches).

On the way home over a week later, after the official tour was over, we drove around Tel Aviv and walked along the Mediterranean Sea, stopping along Jaffa and other major places of interest. While this helped us get a feel for the “secular” tone of modern Israel, it did nothing, of course, to restore any kind of real, authentic historical knowledge for the indigenous peoples that were displaced. We quickly came to realize how many of the names were changed (precisely to make it difficult to reconstruct history from the perspective of the oppressed).

Perhaps our most precious moment of the trip was in Jordan. It wasn’t touching the sacred stones in the Nativity Church or Holy Sepulchre, or even walking alongside the walls of the Jerusalem Temple Mount. It was a 30-minute tea with the Muslim family a block or two from our hotel. There, we actually got to spend time with ordinary people—complete strangers on the street that invited us in (and only two knew English). In that brief time huddling around a television on the floor, we felt the warmth of our drink, the smiles of curious children across the room, and the knowledge that “the Arabs and Muslims are gonna kill you for being American” is as ridiculous and disconnected from reality as it sounds.

Yet, there is seemingly no reason for such people to invite ignorant, well-to-do, dumb tourist white young people like Jessica and I into their homes except giving us the benefit of the doubt, and being kind. And that’s all it was in the end: an expression of love and hospitality towards strangers. And in such moments (rare for many of us), and in that holy place, we encountered the universal Christ.

Special Thanks

To Jay Johnson and Adam Ramirez in proofing this essay and offering feedback, and Kristopher Walhof for bringing my attention to a graphic on progress of Palestinian eradication on Facebook that I had not seen before.

Recommended Reading

For those pressed for time, the two most important books on this subject are (from my view and to the probable audience of curious Christians and onlookers) the following:

Burge, Gary. Whose Land? Whose Promise?: What Christians Aren’t Being Told About Israel and the Palestinians. Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 2013.