My article “The Emphatic Hypernegation That Was(n’t): Revisiting οὐ μὴ and New Testament Translation in Light of Research and Contemporary Linguistics” was just published. The abstract is as follows:

The pleonastic hypernegation οὐ μὴ is widely recognized as conveying an emphatic “no.” However, all major English translations fail to render it consistently with such emphasis. This article explores the nature of this disparity by locating οὐ μὴ linguistically, semantically, and lexically within New Testament literature and contemporary research. It concludes that, despite theoretical exceptions and the erroneous trend of translations, οὐ μὴ should, in the New Testament, always be rendered with some explicit emphasis.

It took about 8 years to write, four years to publish, and two disheartening rejections. But, finally, it now has a permanent home in the world’s number 1 journal on Bible translation. I can’t tell you how relieved I am to be moving on. Here’s the brief story…

The (Relatively Boring) Story to a (Relatively Interesting) Article

It all began on a smelly day on the hog-confinement-surrounded campus of Dordt University (then, Dordt College). I was sitting in the undergrad Greek class of Wayne Kobes (Kristin Kobes Du Mez’ father), which I was privileged enough to take 3 semesters of before graduating in December of 2009. We used Mounce’s 2nd edition grammar, and doing all the things that Greek students do: learn vocab, learn grammar, parsing, and lots of translating the New Testament.

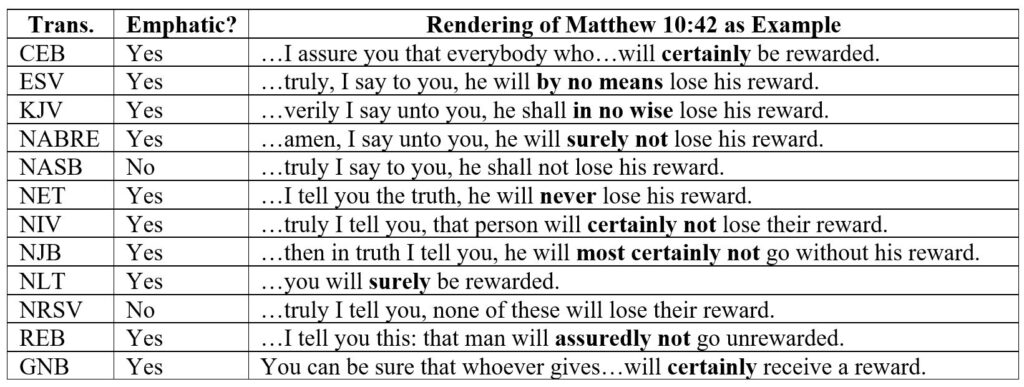

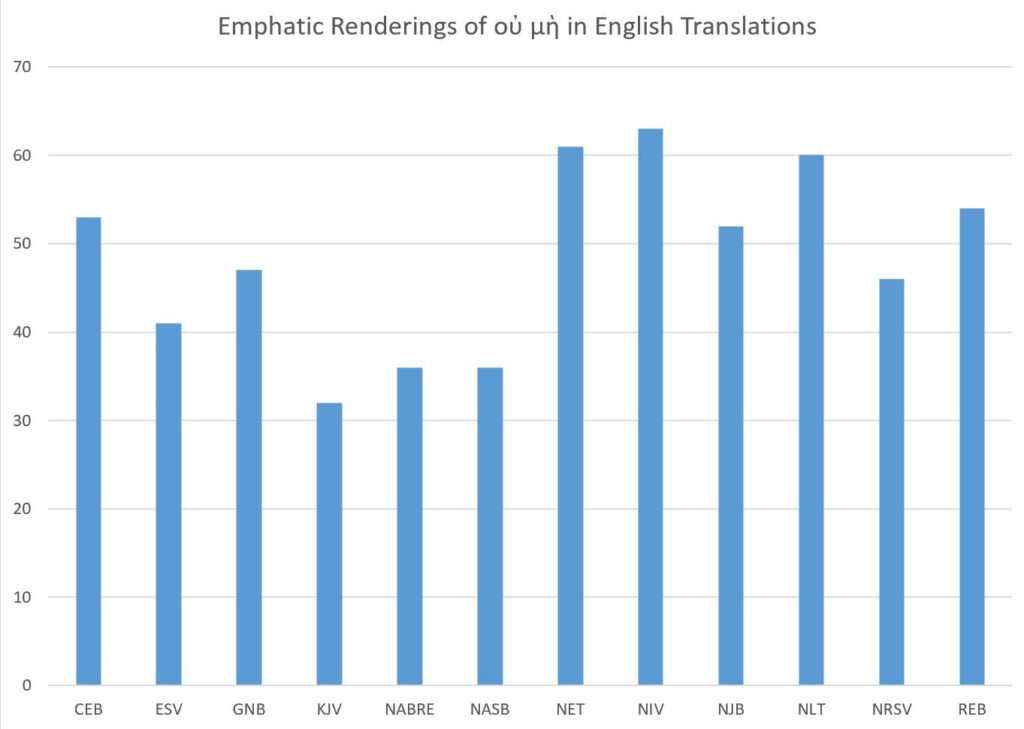

But there was a problem. Many times I would stumble on this idiom, οὐ μὴ, which basically means “hell no!” Our grammar, and our lexicons and reference works, all agreed that it was emphatic negation. “οὐ μὴ: By no means!” I can still remember Professor Kobes saying from the front of the classroom behind the lectern, and looking at some examples. Yet, the English Bibles we held in our hands, no matter what they were, did not render οὐ μὴ with emphasis a good portion of the time. About, say, 20-40%. (The total occurrences in the NT is 95, but as you can see in the graph, no English translation renders it emphatically 95 times).

Why?

There were moments years later that I have wished I wouldn’t have asked this question. I eventually wrote not one, but three different articles on the subject (all essentially re-writes) which failed to get published (the reasons varied: “doesn’t fit our remit” to the all-encompassing and utterly meaningless reply: “we are unable to publish at this time”). I burned through hundreds of dollars purchasing arcane Greek references and recent grammars hoping to find some answers as the project kept evolving—not to mention burning through a ridiculous amount of time. But I just couldn’t seem to bring it together. Dead ends, everywhere. There was no reason why translators failed to heed even their own published advice. What did I really have to say?

It was all too ironic, since my friend and colleague Jeff Miller (Milligan College) had recently published his own article in The Bible Translator of a similar tone and problem. Jeff realized that all textual critics talk about this “rule” in their discipline, “the shorter reading is preferred.” The abstract of the article “Breaking the Rules: Lectio Brevior Potior and New Testament Textual Criticism” is:

Though the principle regarding a preference for the shorter reading is often still included in descriptions of text-critical method, it has fallen out of use. The maxim lectio brevior potior (“prefer the shorter reading”) should not be, and in fact is not, a factor in the modern practice of New Testament textual criticism. This article briefly states reasons for the maxim’s inapplicability and then surveys a large amount of contemporary text-critical and exegetical literature to demonstrate the maxim’s demise.”

In other words, in virtually every textbook on textual criticism, you’ll read about a rule that says “when you encounter two competing readings, the shorter is preferred.” But when you actually look at what textual critics do, they never follow it. It’s just like “normative economics” in the field of economics: economists love talking about it as if it is real and as if it exists, but they never bother with it, because its more of a theoretical fiction that serves a different purpose.

You can see how my problem was a similar situation: everyone is saying “oh yes this idiom should be emphatic!” and then they turn around and render it non-emphatically in every translation written in English for the last 400 years. And better (worse), is that nobody really explains why.

I had nearly given up. But then I found myself along the riverwalk in San Antonio in 2016 having breakfast (and the best Americano of my life, as it turned out) with a wise colleague, Dr. Michael Holmes. Yes, that Michael Holmes: editor and translator of The Early Church Fathers, co-editor with Bart Ehrman of The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research, the guy who blew the lid on false dead sea scrolls at that Bible Museum, textual scholar extraordinaire, etc. He had only one thing to say at this point: “you need to look into linguistics.” And that was enough.

But I wasn’t a linguist. So I educated myself for another year or two and wrote up a small email regarding this problem and sent it to the leading linguists of every big name university I could find.

Predictably, I heard nothing back.

Except for one: Laurence Horn at Yale. Horn was apparently the world’s expert on hyper and double-negation. He was also one of the kindest and most helpful professors in an ivory tower I’ve ever written a random email to. So I read everything he sent me (including an in-depth analysis of the phrase “I don’t give two shits” that made me chuckle), and we geeked out for a few emails before it was time to finally put my thoughts together sometime later.

What Happened

Ultimately, Horn’s rough model of negation was implemented in my article, showing how Koine Greek works within it (e.g., οὐ μὴ should be considered “pleonastic hypernegation”), and how it also clarifies the various ways in which Greek hypernegation functions. Did I find any answers as to why translators failed to render the idiom with emphasis?

Not really. But I did gain new confidence and clarity about its emphatic force, and it also became clear where the article should be published.

So then I finally get the thing into peer review after all these years, and one of the referees doesn’t agree with the methodology, while the other person loves it. Since I suspect I knew who the dissenting peer-reviewer was, I suggested to the general editor to do what was fair, arbitrate disagreement or find an additional peer reviewer if there was any problem or conflict or difficulty in resolving the case (because my new revisions were virtually certainly at odds with the dissenting referee. This was risky. I was essentially doubling down on my approach at the last hour, challenging the logic of a nameless scholar who I couldn’t really satisfy). So that’s what happened, and…the third reviewer really liked it! So it was finally approved, and yesterday, published.

What’s the ultimate value in this project?

Well, first of all, the article re-frames the negation subject in light of Horn’s rather robust linguistic theory of negation, which I think will be helpful for scholars and translators down the road. Most people studying the New Testament simply have little knowledge of linguistics, and that greatly hinders their ability to understand what’s being communicated, how, and why.

Second of all, and more significant: if I’m right, it means all English translations need to be revised for mistranslating οὐ μὴ (failing to translate with emphasis) dozens of times. This could be more significant than it sounds because many of these cases are in the sayings of Jesus, and unless you knew about this issue, you would not know that Jesus was emphasizing the negation. The interpretive—and even the theological implications of this revision, have not yet been explored…