Intended Audience: Those interested in white nationalism, historiography, economic history and revisionism, eurocentrism, and contemporary rhetoric about “western civilization”

Preface

I’ve spent a number of months writing this post, and I’ve finally come to realize why I’m having such a hard time getting it out.

The subject is, uh, a bit awkward—as in “I tried in a single conversation to convince my colleagues who believe that systematic racism doesn’t exist that systemic racism exists, and that it’s way worse than they imagine and negatively affects people every day.” Awkward as in “I tried to convince my husband—who believes patriarchy ceased to exist after women were allowed to vote—in a single text that patriarchy is pervasive throughout history, and it still controls women’s bodies, careers, households, and future prospects today.” Awkward as in “I just wrote an open letter to my boss on my blog explaining how being a boss is inherently exploitative in capitalism, and that profit in business is synonymous with unpaid wages.”

That kind of awkward. It seems hopeless to challenge a way of thinking that has centuries of conditioning behind it in a single effort—especially when my own story proves I’ve been a slow learner. People usually don’t change their minds in a snap; it’s a long process.

I know I can’t expect readers to be automatically sympathetic to my conclusions. Many will always believe that systemic sins, structural evils, social oppressions (whatever words are appropriate) don’t actually exist—or if they do, they’re good. Many people defend patriarchy and sexism as God’s eternal design in one book and conference after another. Many Christians have argued the same regarding the eternal differences in “race.” Entire organizations are dedicated to upholding capitalism as God’s eternal design for economy.

Similarly, Eurocentrism (and with it, Christian Nationalism) is held as a dogma that cannot be questioned (at least not without facing serious consequences). If you’re one of those who agree with that apologetic program, I’m not sure I can help you.

In other words, Eurocentrism is like racism, sexism, and capitalism. We’ve all heard about it, and some of us “woke up” to how it saturates our everyday lives (whether participating in it, enduring it, catalyzing it, or whatever), but few have had the same kind of eye-opening experience with Eurocentrism or “colonialism.” They often mean little to those outside the academy. In my own conversations with colleagues, they tend imagine something like “European bias” in publications, not a worldview that encompasses other movements, ideologies, and social structures like racism, sexism, and capitalism. Indeed, as many historians and social scientists have argued, all four of these systems of oppression complement and reinforce each other. More accurately, Eurocentrism serves as conduit for the more specific programs of social oppression.

“…white supremacist capitalist patriarchal values…” (a famous phrase by bell hooks)

“The forces that impose class injustice and economic exploitation are the same ones that propagate racism, sexism, militarism, ecological devastation, homophobia, xenophobia and the like.” (Michael Parenti)

But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Origins

Months ago, I uploaded a meme on social media and this website of a quote by Andre Gunder Frank’s Re-Orient. My friend, colleague, and former classmate Donald R. (a law prof with an undergrad in history) found it intriguing and asked some basic questions on Facebook. I began crafting a reply but realized it was going to be too long. So here we are. This was supposed to be a Facebook reply.

What follows is my longer reflection on this general subject, which has a brief history in my own professional and intellectual journey. I write it partly to (a) unfold my own developing thoughts on this intersection (I have much not only to process, but new things to learn), (b) provide scaffolding for others in this continuing conversation, (c) demonstrate how easy it is to fall into uncritical study within the academic world, using myself as an example, and, most of all, (d) at least begin to show how pervasive and harmful the world-and-life-view of Eurocentrism (“the colonizer’s model of the world”) is in contemporary society.

I doubt that my own story in “arriving” at a non- (well, anti-) Eurocentric perspective will compel many to join me. My own thoughts are developing, and they reflect my particular experience as a curious theologian-gone-economist. My Lakota and immigrant friends and colleagues have a far more penetrating and insightful perspective on this subject that I’ve just begun to appreciate. Furthermore, I am certain my conclusions are mild in comparison to the realities that they have already experienced and continue to experience, though I know some reading this will find them far too radical for their intellectual framework and professional work.

But, to be frank, I don’t care. I was fired once as a professor for my “unorthodox” publications, and I’m no longer afraid of such coercion. I leave it to my readers to decide for themselves what to think about any potentially disturbing or disruptive material they might encounter along the way. Perhaps some are inspired to learn more about the subject on their own.

Introduction

History—especially economic history—tends to be deeply Eurocentric, and therefore blinded to the realities of the past and how these impact the present. But Eurocentrism isn’t simply a bias. It isn’t a flaw in authorial perspective, and it’s not something that exists only in books and the university.

As many critics argue (compellingly in my view), Eurocentrism is a pervasive worldview: it encompasses the whole and addresses nearly every aspect of our lives, from what we eat to how we work, what religion we adopt or deities we worship, the legal system we live in, the “culture wars,” the very concept of labor.

If you’ve heard former U.S. President Donald Trump talk about “shithole countries,” or heard of Ben Shapiro’s best-seller The Right Side of History: How Reason and Moral Purpose Made the West Great, or remember when the Capitol was stormed by evangelical white nationalists on January 6, 2020, or live in a state that is banning “Critical Race Theory” or any “negative” part of America’s history (or proposing to ban MLK speeches from required readings), or heard white Christian men sound the alarms about plummeting marriage and fertility rates in the West (despite the planet having a whopping 10x the number of humans than a short 300 years ago), then you’re already familiar with Eurocentrism. The “Make America Great Again” program (for example) assumes America is exceptional. Indeed, all of these projects and movements are based not just on American nationalism, but on a larger “west is best” metanarrative.

Eurocentrism is generally defined as a cultural phenomenon that views the histories and cultures of non-Western societies from a European or Western perspective. Europe, more specifically Western Europe or “the West,” functions as a universal signifier in that it assumes the superiority of European cultural values over those of non-European societies. Although Eurocentrism is anti-universalist in nature, it presents itself as a universalist phenomenon and advocates for the imitation of a Western model based on “Western values” – individuality, human rights, equality, democracy, free markets, secularism, and social justice – as a cure to all kinds of problems, no matter how different various societies are socially, culturally, and historically. (Springer, Encyclopedia of Global Justice)

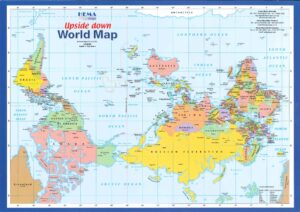

It’s hard to comprehend, but most of modern history (the history that has been perpetuated through the education system not only in the West, but in colonies and ex-colonies) is Eurocentric. It was primarily written by modern Europeans, despite the fact that history doesn’t begin and end with Europe. Europe is literally at the center of the world on most modern maps, which therefore exaggerate its size. Our planet is a sphere with no definitive “center.” Obviously, not everyone on the planet shares the same perspective. Many in India, Africa, South America, and China would not agree with these sentiments about the “West being the best” for countless reasons.

This debate is well-known within history and social scientific circles, and I’ve been vaguely familiar with it since college. But it wasn’t until I started digging into economic history that I realized how bad the problem really is. Like, really bad.

You don’t have to be an academic or a specialist to understand the importance of societal myths. Eurocentrism is heartily defended in contemporary discourse—like in one viral Prager “University” video after the next here in the 21st century.

As a young prof, I would get caught up in one of the most explicit, contemporary Eurocentric projects I could imagine: John Witherspoon College (JWC).

“The West is the Best”?

JWC was founded in 2012 to roll back the clock to the good old days of early America. Students would read what “America’s founders read,” like the “classics” —meaning Greek and Latin works, from Homer and Plato to Augustine and Aquinas. Students would therefore learn Latin and Greek in order to master those “great books.” (If you didn’t know, there are many book series, organizations, conferences, and projects oriented around “the great books” and “Western canon.”) Students at JWC would undertake this education from a conservative evangelical perspective (inerrantist, Zionist, Young-Earth Creationist, complementarian, Republican, etc.) This approach would, in theory, create the best kind of students—the most intelligent, moral, virtuous—who would set out to restore a corrupt and decaying world after graduation.

At the first faculty meeting in a booth at Dunn Bros. Coffee (when it was located on Omaha in Rapid City), founding President Calvin Richard Wells had us read From Dawn to Decadence by Jacques Barzun (a historian who insisted in his opening chapters that he would use androcentric language, because, using “man” to describe God and human beings is “traditional,” and we shouldn’t tamper with these sacred pronouns). We needed to get on the same page about how the West was the best, how it declined, how that threatens the entire planet, and how these realities shaped our mission as educators. This was serious business, after all. Western civilization (whatever that meant) hung in the balance!

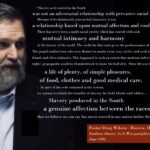

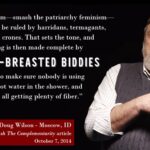

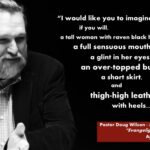

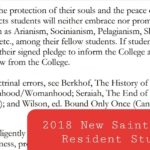

JWC was not the first of its kind, but the third. JWC was modeled after New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho, one of the many projects of the notoriously misogynist cult-leader Douglas Wilson, whose college also tried to duplicate the curriculum and vision of early Harvard and Yale. Wilson even founded an entire “classical education” movement, including schools, organizations, curricula, etc., and authored Repairing the Ruins: The Classical and Christian Challenge to Modern Education. Patrick Henry College near D.C. was another, but with far greater financial support and more programs. By my third or fourth year at JWC, I was growing hesitant about these schools: NSA forbade feminism on campus in its student handbook, its accreditor (which would be ours) was notorious on wikipedia, a breaking story about campus rape on PHC had just been published, and I had just finished my doctoral dissertation to undo the harms of patriarchy in Christianity. (The plot was set!)

I didn’t know about any of this “we’re here to restore Western civilization” stuff when I signed up as a young professor in my 20s. I didn’t even know what that meant…and I’m not sure anyone else did either. I just wanted to teach theology and biblical studies at a university. The heavy orientation on the humanities appealed to me because it wasn’t so focused on churning out students to “get a job” and “make money” in our capitalist, consumerist society. I mean, really, who doesn’t love the humanities? On the other hand, it also felt weird because I never really equated “Western civilization” with “God’s civilization”— God’s special, divinely-blessed vessel through which the whole world would be saved. As a young theologian, it stopped me in my tracks. Was God really absent from the entire world prior to Israel? And was America really God’s chosen nation, like Israel? And if so, maybe this means Europeans really are superior…but doesn’t that dehumanize everyone else? When do non-Christian, non-Europeans finally become fully civilized and fully human?

I gradually came to learn how prominent this orientation was. In conversations with other faculty, they would actually say “the West is best” when, for example, critiquing Susan Bauer’s A History of Ancient Civilization for including whole sections on China. They said chapters on China were “distracting” and “disrupted the larger narrative.” President Wells started an SBC church and hosted Catherine Millard at a conference I attended. She argued all of America’s founders were evangelical Christians. Fundraisers included Michelle Bachmann and sponsors included the Family Heritage Alliance, whose founder was on the board of JWC and later President-elect for a short couple of days before wisely bailing.

It became clear that in these circles, “world” meant “Europe, USA, and ancient Near East.” It had nothing to do with Africa, Asia, India, South America, Indonesia, etc. This was a lesson I encountered over and over again, and I didn’t get it. How could we claim to have a genuine interest in other societies and cultures when we know nothing about them? All our knowledge of the “outside/secular world” came from inside the religious world. One question kept coming back to me: Why is everyone outside this privileged geography habitually excluded?

Oddly enough, in my first year at JWC as faculty (2012), I taught History 101, which was a survey of world civilizations. But because of the chaos of the first year of a new school, I wasn’t actually required to teach the course in any particular way. Since I knew almost nothing about a “classical” approach to history (other than spending my time in the Greco-Roman world and medieval Europe), I decided to choose the most recent, student-friendly textbook on the subject that I could find. That turned out to be A History of World Societies, 9th ed., which was a great survey for students.

The textbook definitely didn’t come from a perspective where Europe is the center of the world and history, where Western civilization is God’s special project, and where all other societies are marginal notes (note this TikTok video mocking this problem via inversion). In teaching the subject, I learned quite a bit about economics and technology when I didn’t expect it. More importantly, I learned a world outside Europe and the U.S. existed, and many things happened during the time of the Old Testament that had nothing to do with the Old Testament (as anyone should generally expect!). Robbed of this “center,” I found new stories and histories and ideas that didn’t fit into “God’s plan” (the history of Israel + Europe). My curiosity only increased.

Compared to What?

Fast-forward to 2015. JWC is struggling to keep the doors open and to keep the “purity” of its original curriculum. (Three years of Latin/Greek? Really? Let’s cut it back.) It was also struggling to exist ideologically as a “liberal arts” higher ed institution in the 21st century. President Wells would endlessly talk about creating an “ancient-future church,” and “we’re trying hard to catch up to the first century,” but what this actually meant was, well, kind of weird.

I discovered that all board members, faculty and staff, were Young-Earth Creationist (YEC, something I was entangled with during high school), and that the accreditor (TRACS) would formally require adherence to YEC once the college became accredited. (Yes, you heard that right: an agency approved by the U.S. Department of Education required all member institutions and staff to be YEC). I also learned that all the “Western values” (or “conservative/family values”) that we needed to restore were basically a combination of patriarchy (male control), white supremacy (white control), colonialism (European control over indigenous lands), homophobia (fear of the gays), pre-modern science (young-earth), Christian nationalism and Zionism. Most of this was implicit, though occasionally explicit. The reality started to dawn on me that I would probably end up leaving or getting fired for not conforming, which probably the end of my career in theology/religion, given the general trends of academia.

So a year after finishing my doctorate, I enrolled in an MS in Applied Economics. I always wanted to study the field more formally, and since econ was part of our core, JWC needed someone to teach the subject for its first graduating class. I quickly met the required 18 credits to teach and finished the online program in 2018 with a project on the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, city revenues, and increasing median age of bikers. It was partly funded by an Acton Institute Economics Mini-Grant—another organization largely aimed at spreading the superiority of Western civilization around the world and allergically reacting towards anything non-conservative. (This is more generous than David Bentley Hart’s assessment: “Acton…[is] a sort of toxic-waste site for the disposal of emotionally arrested and intellectually abridged reactionaries…”). By this time I was writing for the Libertarian Christian Institute because of its nonviolent tradition, discontent with mainstream politics, disloyalty to the two-party system, and focus on economics. I also wanted to get more involved in various issues on whatever platform was welcoming. (I’d later move away from Libertarian circles for reasons similar to leaving JWC—recognizing the problems with market fundamentalisms as a whole, not just their connections to religious fundamentalism). At the time I figured, “Some platform is better than no platform.” (That proved to be a stupid philosophy for my career, and I would advise youngsters against it.)

I taught economics my last year at JWC. I was officially fired Fall 2018 because of the “tone” of my publications on gender. I continued criticizing patriarchy after my doctoral work, though there were other administrative reasons (see here). I learned the meaning of ideological conformity the hard way. After floundering a bit, I began teaching economics at Western Dakota Tech in town. There, with some extra time and the ability to create my own course, I could finally sit down and devour some economic history and try to summarize it in class.

The major question I had at this point was the accuracy of the consensus narrative. That basic historical-economic myth that I had been fed went something like this (to be a bit crass):

- Nothing significant happened for thousands of years, really anywhere (insert long term GDP chart here).

- The industrial revolution happened in “Great” Britain! Why? Easy! Because of their Judeo-Christian values, superior culture and institutions, and because of the kind of people the Europeans were (rational, reasonable, and scientific…definitely not gay and violent…even when many of them actually were.). They also worked really hard! (Hard work is a Western value because, apparently, only Europeans work hard.)

- Anyone who was halfway intelligent copied the Europeans so they, too, could become civilized.

- Nowadays “the West” dominates most of the world, and that’s why everyone is prosperous and happy there.

- (Deduction: Anyone who questions this narrative is a threat to our successful society. Enter the marriage of Trump and evangelicals, Charlottesville protest, January 6 insurrection, anti-CRT legislation and removing material from history classes, anti-trans legislation, sound the alarms about fertility rates of “American” (white) families, bans on women pastors and full-on panic mode of the SBC and TGC in response to Jesus and John Wayne, etc.)

Most of the discourse on economic history was centered around the questions: Why is the West the best? Why are other nations so poor and backward? Asking questions like “What was economic life like in ancient India?” or “How did Africans in the first millennia BCE organize their polity?” or “Why were there wealthy classes of society before capitalism?” already were discounted as unimportant. Although I would ultimately come to very different conclusions than West-is-best apologist Thomas E. Woods, I took to heart his insistent quote that “as long as you’re asking the wrong questions, the answers don’t matter.”

My curiosity only grew when I noticed how the claims of the historical-economic myth either failed to be established in comparison to other civilizations, or the comparisons were clearly superficial and made out of plain ignorance. After all, how can we assert the superiority of an entire civilization (stretching across centuries) without competent, sincere knowledge of others which allow such comparisons?

My dad was (still is) a Certified General Appraiser. His entire business concerns figuring out what something is worth, and that means you need comparables. Even if it’s one house or one acre of land, that could mean weeks of labor, photographs, and research just to construct an idea about its value. The reasoning about civilizations is the same: If you know nothing of other civilizations, you don’t know much about your own. Anyone can say, “I make the best pancakes in the whole wide world!” or, “God blessed me with special intelligence to make these amazing pancakes!” Both are meaningless statements. I can say, “The Vikings are the greatest of all football teams,” but that only means something if I look at the data throughout the history of the NFL and compare them to other teams. Likewise, to say “The West is the best” is to assume prior, comprehensive knowledge of dozens of other societies throughout millennia. Only a true scholar in this field could make this claim.

Furthermore, to say Europeans rule the world because of their “rationality” and “reason” is to imply that everyone else isn’t rational or reasonable. This kind of assertion isn’t an easy dunk, like comparing Soviet communism to 20th century American capitalism. It is a broad generalization about entire peoples. (By this point, I was beginning to see what all this “white supremacy” stuff was that people were arguing about, though it would become more evident later).

The time came to do the homework. After searching and talking to some colleagues, I bought and read a number of books that immediately had a transformative impact on my understanding of world and economic history, although many, if not most, were books I found myself, not those recommended to me.

For example, my understanding of economics was significantly transformed by A History of Economic Thought 3rd. ed. No one told me anti-capitalism was a thing before Marx, that Marx may have had a point as one of the most influential figures in history, that markets based on “voluntary exchange” could actually be coercive, that Christian churches from the 1800s to the present had good reasons to look for alternatives to industrial capitalism, that today’s “orthodoxy” (neoclassicalism) is a product of its time, and on and on. I had taught economics, read all the Acton and Libertarian free market stuff, and attended the Free Market Forum by Hillsdale College. Yet I had to follow Amazon.com’s recommendations to discover that very basic point of elementary understanding. When I dabbled with becoming a Senior Fellow at the Mises Institute, their material again reeked of radical oversimplification and unfamiliarity with non-Western history. I knew this just from teaching HIS101 one time. (That’s not to mention the heavy aura of white supremacy and misogyny; Hoppe isn’t adored by the group and Woods wasn’t best buddies with Molyneux for no reason!).

I had also been reading and publishing in New Testament studies, and the economic situation of the Greco-Roman world was naturally part of that research. I began to see how this ancient world was connected to contemporary Europe and America in its legal and military traditions. I also began to see how definitions of contemporary capitalism (involving markets, trade, exchange, private property, contract law, etc.) were just as easily applicable to the Roman Empire. What then, was this thing called “capitalism”? This is a question I’m still wrestling with as I write a book chapter attempting to answer that question.

In reading Spielvogel’s most recent A History of Western Civilization, I was intrigued by the world of international trade and how much other countries could affect one another. For example:

The Silk Road received its name from the Chinese export of silk cloth, which became a popular craze among Roman elites, leading to a vast outpouring of silver from Rome to China and provoking the Roman emperor Tiberius to grumble that the ladies and their trinkets were transferring money to “foreigners.” The silk trade also stimulated mutual curiosity between the two great civilizations, but not much mutual knowledge or understanding. There was little personal or diplomatic contact between the two civilizations, but Chinese sources do reveal that a delegation from the emperor Marcus Aurelius arrived in China in 166 and that a Roman merchant made it to the court of Emperor Wu in 266. After the takeover of Egypt in the first century C.E., Roman merchants also began an active trade with India, from where they received precious pearls as well as pepper and other spices used in the banquets of the wealthy. The Romans even established a trading post in southern India, where their merchants built warehouses and docks. (Spielvogel, Western Civilization, 11th ed, 161)

This was baffling, since I was always given the impression that international trade was getting off the ground around the 1500s-1800s, not the 200-300s. And I was given the impression that civilizations were isolated units that never really interacted or substantially affected each other until the modern period when people could finally map the world and sail across the ocean. I had no framework with which to make sense of (for example) “trade-wars” in the Ancient World.

“World Economic History”

One of the books actually recommended to me turned out to be the most frustrating—and this is where things really got problematic. It was Larry Neal and Rondo Cameron’s A Concise Economic History of the World, 3rd ed. Here!, I thought, I’ve finally gotten my hands on a survey text specifically on global economic history. This will solve all of my problems! I opened up and skimmed its pages to see what it had to say about ancient India’s economy, ancient China’s economy, ancient Africa’s economy, the evolution of global trade in Asia, the Aztecs and Native Americans, etc. …only to find that it was just another book on industrial England with a few prefaces.

How could this be? I thought. I learned more about world economics when I taught History 101 than in reading the standard text by Oxford University Press on this subject. It was like I had never left JWC. The entire world, and all of human history, was habitually truncated into the activities of a tiny peninsula in a span of maybe 200-400 years. It would be like a book titled, A Biological History of the World that only covered invertebrates in the Indian Ocean. Or something like that. What was clear is that This. Was. Not. World. Economic. History. Was I going crazy?

I was able to cheaply obtain the 5th edition (2016), which actually began to act as if Europe wasn’t the only continent that existed, and that economic history for a species that goes as far back as 300,000 years doesn’t begin in the 1700s or 1800s. But the more I read, the more irritated I became. The gestures were just that—gestures. The authors’ preface this profound embarrassment with the following defense:

The 2nd and 3rd editions appeared in 1993 and 1997. Each one expanded the coverage of non-European economies, trying to keep pace with ongoing globalization.

As if the developments of the last quarter century excuse excising the first 5000 years of global economic history, and then adding non-European content at the beginning of the volume!

Neal then argues that the book’s focus on Europe and it’s “success” is justified because it helps maintain a “narrative arc,” and has “accessibility to undergraduates.” In other words, “this book on global economic history has always been centered on Europe; we added non-European stuff to satisfy critics, but maintain this Eurocentric perspective because” (just like I was told by a JWC faculty) “it tells a better story.” After all, we wouldn’t want to confuse students by talking about economies and worlds and societies and global trade networks that they might be unfamiliar with!

As you can tell, my BS meter was really going off. The authors didn’t expand coverage of non-European economies because they existed for thousands of years, are well documented, determined Europe’s future and the development of the modern world, and continually have been studied by (apparently a rogue and minority of) economic historians. None of this was a sudden revelation. Rather, other countries became relevant when they (allegedly) started trading more with Europe. Who cares about other countries trading and developing economically with each other? What relevance does that have? (The question reminds me about Josh McDowell’s “apology” for his racist remarks that pulled him out of ministry: he never acknowledged his racism and how its affected his whole perspective, or how he’s going to learn and correct from these mistakes. He simply placated critics.)

Lest you think this is too assuming or critical, consider the first paragraph of the book, which has an all-too-familiar tone:

Why isn’t the whole world developed? That question has plagued humankind for thousands of years, but especially over the past three centuries, when the economic performance of Europe became uncoupled from that of the rest of the world…The issue became ever more urgent with the spread of capitalism globally after the fall of the Berlin Wall… (p. 1).

On the contrary, this question has not plagued humankind for thousands of years. How could it when (according to the same authors) the world wasn’t developed until recently? I can assure you, King Tut was not sitting on his throne thinking, “Gosh, I wonder how those Natives in America got such high GDP?” or “When are we finally going to get economically developed?” Nor were Asians in the 1600s thinking, “Golly, Europe is so much more rich than all us. Why!?” This wasn’t a historical framework; it was a fictional framework. As many other historians have suggested, should the Apache, Lakota, and Sioux have gained knowledge about Europe during the early Industrial period, they would have probably wondered, “Why the hell are they throwing their own feces into the streets from apartment windows and killing everyone with disease?” (Actually, indigenous peoples did ask these kinds of questions about European settlers from the 1600s-1800s, particularly about why they were so violent when it came to economic trade.)

My point is that no person trying to be halfway objective would begin an economic history of the world with a question like this without assuming a Eurocentric/neoliberal account of development (which frames European Industrialism as the beginning of economic development, and all previous societies as “undeveloped”). An author would (should) ask something less loaded like, “When did the first economies develop?” or “How did the first economies develop, and what were they like?” Even, “What is economic development?”

Less than a page later, no “world economic history” textbook is complete without an immediate reference to the falling of the Berlin Wall—the ultimate symbol of Western liberal representative capitalist democracy’s triumph over the world. That’s the primary point of “global economic history.” Never mind icons like the invention of the wheel, fire, the invention of writing, the Silk Road, the end of African apartheid, the Haitian Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the French Revolution, the abolition of the slave trade, Sitting Bull’s victory over the American army, the capitulation of Constantinople to the Ottomans, the completion of the Egyptian pyramids, Haymarket murders in Chicago, the civil wars between Genoa and Venice in the Mediterranean, etc. No, none of those things qualify as icons or key events in economic and social history—the vast majority of which are never mentioned in Neal’s volume at all, because, he’s right: they wouldn’t fit.

It was around this time that I also began to try to figure out what “colonialism” meant. I felt like this 500-year project was somehow important for understanding the last 500 years of economic history. But the economists and economist historians that I had read up to this point didn’t feel that way; they kept dodging it, being coy and muttering obscure footnotes in hushed tones—as if something was important, but they just didn’t want to talk about it. This piqued my curiosity even more.

I remembered Professor Keith Sewell at Dordt giving me a small book on “colonialism” from college because he thought it was important for me to read. For reasons I don’t recall, I gave it to the thrift store. I wouldn’t revisit that subject directly until years later.

Slowly Re-Orienting

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a couple things happened.

First, I wrote (apparently the longest) article published in the journal Faith and Economics—”Owning Up to It: Why Cooperatives Create the Humane Economy Our World Needs.” Worker coops were something of a revelation for me, as I had always been consumed with the idea of decentralized/distributed power since (1) watching one church fall apart after another because of pastors with too much power and dysfunctional elder boards, and (2) learning about the latest inequality statics in a global capitalist world. This decentralization focus was partly what led me into libertarian circles to begin with. Good ole Lord Acton, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely…so then how in the world do we de-absolutize and de-centralize power?

But what this article allowed me to do was dig into the history of workers movements, socialism, anarchism, which once again, left me confused in all sorts of ways…and they weren’t conducive to my right-leaning free-market ideologies.

For example, it wasn’t until I read Proudhon’s Property is Theft! (can you imagine me reading a book with that title as a post-Rothbardian of only two years?) that I learned how “libertarian” meant “anti-state socialism” for nearly a century, across countries. (Still today, in fact, scholars and economists outside of the US use the term to refer to individualist Marxism/anarchism/socialism.) “Libertarianism” never meant what it means today (right-wing, pro-capitalist, small government) until around the World War period. (This is a fact iterated over and over in various reference works because today’s libertarians are so oblivious to it, and because the discourse in America about the term is equally ignorant.)

I also learned more and more that the state was not so much an isolated devil and source of all evil, but rather a tool in the hands of the wealthy. As a provisional libertarian, I had a framework that explained tax revolts, but not a framework that explained slave rebellions and worker strikes at the same time (other than, “they’re just being lazy, and jealous of their billionaire bosses”). That is, I didn’t have a framework that explained capitalist violence, capitalist coercion, and capitalist centralized power, which I was learning was more of the norm than the exception. One of my footnotes in “Owning Up to It” is a big list of such massacres of workers who refused to be dehumanized and exploited by their employers. (How could any of this happen if all of these relationships were “mutual” and “voluntary”? And when I read Rudolph Rocker’s Anarcho-Syndicalism soon thereafter and realized capitalism and statism are two forms of economic exploitation that have worked side-by-side as partners for centuries, my whole world was turned upside down…)

Second (and related), I realized that I was just really ignorant of economic history proper, and it was time to dive in. But where was I to go?

Amazon, I guess? And there I found a Harvard prof’s bestseller called The Wealth and Poverty of Nations.  With a title like that, surely it would measure up to high standards and provide a firm foundation for orienting myself around this whole subject.

With a title like that, surely it would measure up to high standards and provide a firm foundation for orienting myself around this whole subject.

Big mistake. It wasn’t just Eurocentric, it was fanatically Eurocentric. The author, David Landes, literally says in the introduction, “Some say Eurocentrism is bad…As for me, I prefer truth to goodthink” (p. xxi). James Blaut summarizes (in a book I’ll mention later) what that amounts to:

Landes’s “truth,” however, looks very ideological. For instance: “[The] very notion of economic development was a Western invention” (p. 32). “Over the thousand and more years of…progress…the driving force has been Western civilization and its dissemination” (p. 513). “Sub-Saharan Africa threatens all who live or go there” (p. 8). African farmers prefer large families as “proof of virility” (p. 501). “Chinese lacked…curiosity” (p. 96). “Chinese sevants had no way of knowing when they were right” (p. 344, emphasis in the original); “unlike China, Europe was a learner” (p. 348). In Latin America, “the skills, curiosity, initiatives, and civic interests of North America were wanting,” and “independence slipped in [as] a surprise to unformed, inchaote entities that had no aim but to change masters” (p. 313). Japanese have exhibited a “characteristic ferocity” (p. 355). Indians (before British rule) were “a docile people” (p. 396). “Even if Israel did not exist, [the Arabs] would be at one another’s throats” (p. 409). And so on. (Blaut, Eight Eurocentric Historians, 173-74)

This was one of the very few books (of any kind) that I couldn’t finish. I plowed through half of it until I got sick from so much racism (in my view, Blaut is more generous), arrogance, contradictions, and horrible writing style that I just couldn’t take it anymore. I mean, some things were fascinating…but why did it felt like all of the outcomes were predetermined? Like I was reading, well, something bordering fiction?

I kept doubting myself. “It’s rated so well,” “it’s sold so many,” “he teaches at Harvard,” “the name is great,” etc. Maybe he was right, and the west simply is the best? Maybe all the other countries but modern Europe had always been backward, dumb (uninventive, uncurious, non-innovative, etc.). But, my gut kept telling me that I was right. Something was off in the same or similar way that Neal’s Economic History of “the World” as off. (Side note: I later learned that Landes’ book was quoted extensively in Wayne Grudem’s The Poverty of Nations. No surprises there.).

So I picked the book back up and looked at footnotes when Landes explicitly defended his Eurocentric theses so I could see who he was responding to. The least I could do was intentionally read the other side, even though Landes’ was confident they had nothing meaningful to say. (It reminded me how I used to trust Grudem’s confidence that Rebecca Groothuis and other egalitarians have nothing meaningful to say and no good arguments; but that Proverb, “The first to plead a case seems right…” always came back to bite!). I kept seeing the name “Andre Gunder Frank” popup.

Frank apparently wrote a book basically the same time as Landes’s icky volume. It was entitled Re-Orient. It’s the book at the top of this log post.

And within reading the first page of Frank’s “life’s work,” I was gripped. I finally learned that I wasn’t crazy, and I wasn’t alone.

Re-Orient

Asia, not Europe, was the centre of world industry throughout early modern times. It was likewise the home of the greatest states. The most powerful monarchs of their day were not Louis XIV or Peter the Great, but the Manchu emperor K’ang-hsi (1662-1722) and the “Great Moghul” Aurangzeb (1658-1707).

Times Illustrated History of the World (1995:206)

This quote in Andre Gunder Frank’s Re-Orient: Global Economy in the Asian Age was the second of many more confirmations that, paradoxically, to find sound economic history, one must avoid economic history (which tends to be hopelessly Eurocentric and imbibed in various popular myths; cf. “The Colonizer’s Model of the World” below). One must instead read world history proper—just as I had teaching HIS101.

The title Re-Orient plays off of two common phenomena: Eurocentric map-making (which needs to be re-oriented), and Europeans’ continual degradation of Asians (“the Orient”) through a specific trope called “Oriental Despotism.” “Oriental Despotism” is the European myth that Asians (i.e., Japanese, Chinese, Indians) don’t really care about freedom, were always authoritarian, and generally sucked as a people for those kinds of reasons. It’s exactly what Landes (among others) argued over, and over again throughout his publications.

But Frank—a former Chicago-school neoliberal who woke up (yes, I’m using the word “woke”! Feel free to substitute with more biblical language, like “born again” if woke is too triggering)—opened my eyes to larger dynamics and larger problems beyond the same old discourse. This was due to his methodology and approach (and that of others) called “world systems theory.”

World Systems Theory basically proposes that the world operates like an interconnected organism, so that if you touch or affect one part, you touch or affect the rest. While most economic historians would agree to this when Britain rose to power and also make it a feature of the modern world, Frank argues that it was almost always the case, especially in 1400-1800 (which is pre-industrial, pre-British hegemony).

This means that we cannot understand what happened in modern Europe without understanding what was happening elsewhere. As he writes in the first page:

I seek to analyze the structure and dynamic of of the whole world economic system itself and not only the European (part of the) world economic system. For my argument is that we must analyze the whole, which is more than the sum of its parts, to account for the development even of any of its parts, including that of Europe. That is all the more so the case for “the Rise of the West,” since it turns out that from a global perspective Asia and not Europe held center stage for most of early modern history…I…propose to account for “the Decline of the East” and the concomitant “Rise of the West” within the world as a whole. This procedure pulls the historical rug out from under the anti-historical/scientific–really ideological–Eurocentrism of Marx, Weber, Toynbee, Polanyi, Braudel, Wallerstein, and most other contemporary social theorists. (Frank, Re-Orient, Preface)

As I’d later learn (see “The Colonizer’s Model of the World” and “China” below), Europe essentially became great not simply by internal changes (decline of manorialism, rise of common law, inventions), but by (a) 500 years of colonialist exploitation, (b) 400 years of slave trade and slave labor, (c) exploiting Asian economic superiority for their own benefit. Because this isn’t the story they wanted to tell about their “civilization” (indeed, it’s all about as barbaric and violent as one can imagine), the colonizer (Europeans, or white males with power) must write history as if Europe was culturally, economically, intellectually, and socially superior to the rest of the world prior to this period of colonization. The trouble there is, this is a very difficult argument to make, and we’re back into mythology.

Europe did not pull itself up by its own economic bootstraps, and certainly not thanks to any kind of European “exceptionalism” of rationality, institutions, entrepreneurship, technology, geniality, in a word—of race…Europe used its American money to muscle in on and benefit from Asian production, markets, trade—in a word, to profit from the predominate position of Asia in the world economy. Europe climbed up on the back of Asia, then stood on Asian shoulders—temporarily.

…Europe was certainly not central to the world economy before 1800…In no way were sixteenth century Portugal, the seventeenth century Netherlands, or eighteenth century Britain “hegemonic” in world economic terms. Nor in political ones. None of the above! In all these respects, the economies of Asia were for more “advanced,” and its Chinese Ming/Qing, Indian Mughal, and even Persian Safavid and Turkish Ottoman empires carried much greater political and even military weight than any or all of Europe. (5)

For Frank, Europe came to economic dominance not just through centuries of foreign exploitation, but particularly through the silver market with the Orient (Europeans had indigenous and African slaves mine the silver and gold in the Americas, and then traded the silver with Asia for insane values that helped finance the industrial revolution and their warfare-ready economy as a whole).

Frank looks at newspaper articles and publications that ask the question, “how did China today become so great without European capitalism”? Indeed, there are endless books currently being published on this very subject: we all know Europe is the greatest, and basically always has been, so what’s up with the Chinese, ruled by the communist party? But, this is again a case study in asking the wrong question…

Others have sought and offered all manner of “explanations” for this Asian awakening, from “Confucianism” to “the magic of the market without state intervention.” Alas, the contemporary East Asian experience does not seem to fit very well into any received Western theoretical or ideological scheme of things. On the contrary, what is happening in East Asia seems to violate all Western canons of how things “should” be done, which is to copy how “we” did it in the “Western way.” (Re-Orient, 7)

Something more interesting I learned in Frank’s book is how pervasive Eurocentrism is in Marxism and classical economics. The Communist Manifesto adopts the very same perspective as Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations: the “discovery” of America and European colonization was not only the most economically significant series of events in recent times, but perhaps the most significant in all of human history (see p. 13). Marx and Smith make all kinds of the same fallacies in characterizing Europe’s uniqueness (many summarized below in “Appendix A”). Indeed, “Marxist economic history may seem different, but it is equally, indeed even more, Eurocentric. Thus, Marxist economic historians also look for the sources of ‘the Rise of the West’ and ‘the development of capitalism’ within Europe'” (p. 26). In looking back at Hunt and Lautzenheiser’s History of Economic Thought, I was realizing how this problem affected their work as well (in specific ways I won’t here elaborate)—and as Frank goes on to show, of Max Weber and numerous other intellectuals in the social sciences.

As I said, I started not to feel so crazy. Frank plainly states: “One might naively think that for the study of economic history as it really was, the place to turn is to economic historians. Yet they have been the worst offenders of all. The vast majority of self-styled “economic historians” totally neglect the history of most of the world, and the remaining minority distort altogether” (p. 25). Exactly! And in support of this assertion, Frank examines several texts and works that I had never heard of or read, which means my suspicions of this problem from the small selection of books I had read was, indeed, probably representative of the field in general.

He also shows how persistent historians and economists are in maintaining their Eurocentrism and ignoring the rest of the world to prove their own theses. As he summarizes:

[First] Eurocentrists refuse to make and are reluctant even to accept comparison with other parts of the world, which reveal similarities not only in institutions and technological but also in the structural and demographic forces that generated them. Second…these comparisons show that the alleged European exceptionalism was not exceptional at all. Third, the real issue is not so much what happened here or there, but what the global structure and forces were that occasioned these happenings anywhere… (p.25)

These are but summaries of what Frank demonstrates in his seminal book. It was definitely enough to keep me interested, and falling further down the rabbit hole…

The Colonizer’s Model of the World

As far as social theory goes, Frank leaned on James Blaut’s seminal work The Colonizer’s Model of the World. With a title like that, I had to pick it up. But I should note first that it was a revision an expansion of the earlier book 1492: The Debate on Colonialism, Eurocentrism, and History. There, Blaut lays out some of his basic theses, including the idea that European modern success was largely due to their colonial ventures (this was something iterated with reference to Africa in the brilliant work by Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa written in 1972). Then, several authors (Frank and four others) respond to it. The Colonizer’s Model of the World is Blaut’s response to this conversation.

I wish I read it first (and earlier). It knocked me off my rocker. Reading The Colonizer’s Model of the World was one of the most Matrix-unplugging experiences I’ve ever had. Which is pretty wild given how eye-opening Re-Orient was.

Blaut’s first thesis was: the colonizer’s model of the world is eurocentrism. In other words, Eurocentrism is not a mere vestige of bias dwelling in the academy and in economic history. It is a worldview forged out of physical, economic conditions, events, flesh and blood people—to affect our material world again, and again, in very specific and verifiable ways. Eurocentrism was the soil and fertilizer out of which modern racism, sexism, and capitalism sprouted. Blaut’s second thesis was that the “European miracle” is a fiction. Let’s look at each of these a little closer, starting with the latter…

The myth of the European miracle is the doctrine that the rise of Europe resulted, essentially, from historical forces generated within Europe itself; that Europe’s rise above other civilizations, in terms of level of: development or rate of development or both, began before the dawn of the modern era, before 1492; that the post- 1492 modernization of Europe came about essentially because of the working out of these older internal forces, not because of the inflowing of wealth and innovations from non-Europe; and that the post- 1492 history of the non-European (colonial) world was essentially an outflowing of modernization from Europe.

The core of the myth is the set of arguments about ancient and medieval Europe that allow the claim to be made, as truth, that Europe in 1492 was more modernized, or was modernizing more rapidly, than the rest of the world. This is a myth in the classical sense of the word: a story about the rise of a culture that is believed widely by the members of that culture. It is also a myth in the sense of the word that implies something not true. (The Colonizer’s Model of the World, 59)

I mentioned this earlier, but perhaps it makes more sense now: Europe achieved economic dominance in the 1800s and following largely because of 400 years of imperialism, exploitation, and extracting slave labor from indigenes and African Americans. Because this is neither a pleasant history, nor one that bolster’s a “civilized” narrative, European intellectuals forged a false (or at least highly misleading) history that Europe was superior to everyone before, during, and after colonialism, so whatever gains came from colonialism were superfluous.

Furthermore, this fiction argues in favor of diffusionism—the idea that wherever we find economic, social, religious, or political superiority in the world today, we can assume it all came from Europe. (It’s like some of the shoddy arguments that popular critics of the historical Jesus make when trying to make early Christianity out to be nothing but a rip off of previous Greek mythologies/religions). “My basic argument,” writes Blaut, “is this: all scholarship is diffusionist insofar as it axiomatically accepts the Inside-Outside model, the notion that the world as a whole has one permanent center from which culture-changing ideas tend to originate, and a vast periphery that changes as a result (mainly) of diffusion from that single center” (p. 13). This is in contrast to, well, “better history” (or at least more “critical history”) that notices how societies can and regularly do (for example) develop the same technologies and same religious ideas independently, without a “source” and a “receiver.”

This seems straightforward enough, but this argument challenges more orthodoxies of modern history than we realize:

Most European historians still maintain that most of the really crucial historical events, those that “changed history,” happened in Europe, or happened because of some causal impetus from Europe. (“Europe” continues to mean “Greater Europe.”) To illustrate this fact, I will list now, in historical order, a series of crucial Europe-centered propositions. All of them are accepted as true by the majority, in some cases the great majority, of European historical scholars. Some of them indeed are true, but that is beside the present point, which is to show that historical reasoning still focuses on Greater Europe as the perpetual fountainhead of history.

- The Neolithic Revolution — the invention of agriculture and the beginnings of a settled way of life for humanity — occurred in the Middle East (or the Bible Lands). This view was unopposed before about 1930, and is still the majority view.

- The second major step in cultural evolution toward modern civilization, the emergence of the earliest states, cities, organized religions, writing systems, division of labor, and the like, was taken in the Middle East.

- The Age of Metals began in the Middle East. Ironworking was invented in the Middle East or eastern Europe and the “Iron Age” first appeared in Europe.

- Monotheism appeared first in the Middle East.

- Democracy was invented in Europe (in ancient Greece).

- Likewise most of pure science, mathematics, philosophy, history, and geography.

- Class society and class struggle emerged first in the Greco-Roman era and region.

- The Roman Empire was the first great imperial state. Romans invented bureaucracy, law, and so on.

- The next great stage in social evolution, feudalism, was developed in Europe, with Frenchmen taking the lead.

- Europeans invented a host of technological traits in the Middle Ages which gave them superiority over non-Europeans. (On this matter there are considerable differences of opinion.).

- Europeans invented the modern state.

- Europeans invented capitalism.

- Europeans, uniquely “venturesome,” were the great explorers, “discoverers,” etc.

- Europeans invented industry and created the Industrial Revolution. . . . and so on down to the present.

All of the propositions in this list are widely accepted tenets of European historical scholarship today, although (as we will see) there is scholarly dispute about some of the propositions. All of this means that you and I learned these things, perhaps in elementary school, perhaps in university, perhaps in books and newspapers. We learned that all of this is the truth. But is it?” (The Colonizer’s Model of the World, 7-8)

These are just a handful of propositions, but they were validating the suspicions I had over the last half-decade.

That brings us to Blaut’s second major thesis, which is that Eurocentrism is not just a slight bias in our thinking, but a comprehensive framework for looking at the world. This is a lengthy quotation, but it’s the highlight of this entire post, and it’s the author’s own concise summary, so don’t rush it (pp 14-17):

The basic model of diffusionism in its classical form depicts a world divided into the prime two sectors, one of which (Greater Europe, Inside) invents and progresses, the other of which (non-Europe, Outside) receives progressive innovations by diffusion from Inside. From this base, diffusionism asserts seven fundamental arguments about the two sectors and the interactions between them:

- Europe naturally progresses and modernizes. That is, the natural state of affairs in the European sector (Inside) is to invent, innovate, change things for the better. Europe changes; Europe is “historical.”

- Non-Europe (Outside) naturally remains stagnant, unchanging, traditional, and backward. Invention, innovation, and change are not the natural state of affairs, and not to be expected, in non-European countries. Non-Europe does not change; non-Europe is “ahistorical.”

Propositions 3 and 4 explain the difference between the two sectors:

- The basic cause of European progress is some intellectual or spiritual factor, something characteristic of the “European mind,” the “European spirit,” “Western Man,” etc., something that leads to creativity, imagination, invention, innovation, rationality, and a sense of honor or ethics: “European values.”

- The reason for non-Europe’s nonprogress is a lack of this same intellectual or spiritual factor. This proposition asserts, in essence, that the landscape of the non-European world is empty, or partly so, of “rationality,” that is, of ideas and proper spiritual values. There are a number of variations of this proposition in classical (mainly late- nineteenth-century) diffusionism. Two are quite important:

- For much of the non-European world, this proposition asserts an emptiness also of basic cultural institutions, and even an emptiness of people. This can be called the diffusionist myth of emptiness, and it has particular connection to settler colonialism (the physical movement of Europeans into non-European regions, displacing or eliminating the native inhabitants). This proposition of emptiness makes a series of claims, each layered upon the others: (i) A non-European region is empty or nearly empty of people (hence settlement by Europeans does not displace any native peoples), (ii) The region is empty of settled population: the inhabitants are mobile, nomadic, wanderers (hence European settlement violates no political sovereignty, since wanderers make no claim to territory, (iii) The cultures of this region do not possess an understanding of private property — that is, the region is empty of property rights and claims (hence colonial occupiers can freely give land to settlers since no one owns it). The final layer, applied to all of the Outside sector, is an emptiness of intellectual creativity and spiritual values, sometimes described by Europeans (as, for instance, by Max Weber) as an absence of “rationality.”

- Some non-European regions, in some historical epochs, are assumed to have been “rational” in some ways and to some degree. Thus, for instance, the Middle East during biblical times was rational. China was somewhat rational for a certain period in its history. Other regions, always including Africa, are unqualifiedly lacking in rationality.

Propositions 5 and 6 describe the ways Inside and Outside interact:

- The normal, natural way that the non-European part of the world progresses, changes for the better, modernizes, and so on, is by the diffusion (or spread) of innovative, progressive ideas from Europe, which flow into it as air flows into a vacuum. This diffusion may take the form of the spread of European ideas as such, or the spread of new products in which the European ideas are concretized, or the spread (migration, settlement) of Europeans themselves, bearers of these new and innovative ideas.

Proposition 5, you will observe, is a simple justification for European colonialism. It asserts that colonialism, including settler colonialism, brings civilization to non-Europe; is in fact the natural way that the non-European world advances out of its stagnation, backwardness, traditionalism. But under colonialism, wealth is drawn out of the non-European colonies and enriches the European colonizers. In Eurocentric diffusionism this too is seen as a normal relationship between Inside and Outside:

- Compensating in part for the diffusion of civilizing ideas from Europe to non-Europe, is a counterdiffusion of material wealth from non-Europe to Europe, consisting of plantation products, minerals, art objects, labor, and so on. Nothing can fully compensate the Europeans for their gift of civilization to the colonies, so the exploitation of colonies and colonial peoples is morally justified. (Colonialism gives more than it receives.)

And there is still another form of interaction between Inside and Outside. It is the opposite of the diffusion of civilizing ideas from Europe to non-Europe (proposition 5):

- Since Europe is advanced and non-Europe is backward, any ideas that diffuse into Europe must be ancient, savage, atavistic, uncivilized, evil — black magic, vampires, plagues, “the bogeyman,” and the like. Associated with this conception is the diffusionist myth which has been called “the theory of our contemporary ancestors.” It asserts that, as we move farther and farther away from civilized Europe, we encounter people who, successively, reflect earlier and earlier epochs of history and culture. Thus the so-called “stone-age people” of the Antipodes are likened to the Paleolithic Europeans. The argument here is that diffusion works in successive waves, spreading outward, such that the farther outward we go the farther backward we go in terms of cultural evolution. But conversely, there is the possibility that these„ ancient, atavistic, etc., traits will counterdiffuse back into the civilized core, in the form of ancient, magical, evil things like black magic, Dracula, etc.

The main oppositions between the two sectors can be shown in tabular form. The following contrast-sets are quite typical in nineteenth- century diffusionist thought:

Characteristic of Core Characteristic of Periphery Inventiveness Imitativeness Rationality Intellect Irrationality emotion instinct Abstract thought Concrete thought Theoretical reasoning Empirical, practical reasoning Mind Body, matter Discipline Spontaneity Adulthood Childhood Sanity Insanity Science Sorcery Progress Stagnation

This was written in 1994, and it still explains everything about Ben Shapiro’s The Right Side of History, Samuel Gregg (Acton Institute)’s book Reason, Faith, and the Struggle for Western Civilization, Thomas Woods’ How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization and The Church and the Market: A Catholic Defense of the Free Economy, Rodney Stark’s How the West Won and The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success, Daron Acemuglu and James Robinson’s Why Nations Fail, Niall Ferguson’s Civilization: The West and the Rest, and a hundred other similar volumes of intellectual propaganda people (the vast majority of whom are white Christians in America) are reading, tweeting, and trying to apply today.

Blaut demonstrates all seven of these arguments in his work, case by case, book by book, historian by historian. He originally planned three volumes for this project, but died unexpectedly right after submitting the second volume in the year 2000 (Eight Eurocentric Historians; highly recommended). Thankfully, the first two are generally adequate to get the message across.

As an American speaking English and growing up Protestant, heterosexual, male, etc., I found that Blaut’s analysis had the unexpected effect of re-orienting and reshaping my understanding of myself, my role in this larger system and larger worldview, in western society. These frameworks and social structures are perpetuated by almost everyone, but are protected and upheld especially by those who benefit from them. This invoked a new sense of responsibility in relation to privileges and whatever powers I have. (Insert “History Matters” bumper sticker here.)

In any case, a 2014 review of The Colonizer’s Model of the World has it right:

Looking back, it is remarkable how little Blaut’s arguments about Eurocentrism have impacted Western mainstream thinking on international affairs. Popular books that seek to explain the rise of the West — such as Larry Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel or Ian Lewis’ Why the West rules – for now — are strongly influenced by geographic determinism and do not even mention Blaut’s arguments. The concept of Eurocentrism itself remained limited to a relatively small group of academics. That may be because, as Blaut puts it, “the critique of diffusionism has barely begun.”

Interim to the Present

If you’ve stuck with me for this long, I have good news: we’re not done!

Over the first phases of the COVID 19 pandemic, I realized I would be writing a book on cooperative economics that had a chapter on economic history. This was an excuse to go down the rabbit hole even further and see if I missing anything, or completely off base. I started publishing reviews from an anti-Eurocentric perspective (see here, and many forthcoming yet, including one on the 2021 monograph The Economic History of Colonialism for Capital & Class, which was Eurocentric in several key ways. Like, writing from the perspective of the colonizer, and excluding almost everything prior to the British empire; nothing out of the ordinary for economic history!). And out of several dozen volumes I’d devour, a few are worth brief mention since they are the result of a particular inquiry.

Basically, Frank and Blaut opened a whole new world open to me. And that world wasn’t large, because it was the world of non-Eurocentric economic history. But it was large enough that it got me asking: are there any English-language textbooks on economic or general history with reference to major economic aspects that are intentionally non-Eurocentric? Because I already owned and read a number of ones that failed that test (books that will hopefully someday serve as nothing more than a floppy paperweight). And I’d be curious if those in the industry of “being up-to-date” would produce intentionally non-Eurocentric works.

I found some. One was a 2018 publication by Cengage (my favorite textbook publisher) called Global Americans. The book provides an alternative history of America (competing against other texts by Cengage, in fact), as the preface remarks:

In their form and content, most textbooks portray the United States as a national enterprise that developed largely in isolation from the main currents of world history. In contrast, this textbook speaks to an increasingly diverse population of students and instructors who seek to understand the nation’s place in a constantly changing global, social, and political landscape. It incorporates a growing body of scholarship that documents how for five centuries North America’s history has been subject to transnational forces and enmeshed in overseas activities and developments. American history was global in the beginning, and it has been ever since. We therefore present a history of the United States and its Native American and colonial antecedents in which world events and processes are central features, not just colorful but peripheral sidelights. (Montoya et. al, Global Americans, xxi)

I’ve been using this wonderful, fully colored text ever since. (You should too…but ignore the typo about the Torah being written 3000BCE on page 36, lol).

Another is Heather Street-Salter and Trevor Getz, Modern Empires and Colonies in the Modern World: A Global Perspective (Oxford, 2016). The second chapter was impossible to follow and I nearly gave up. But for some reason, the prose and organization whipped into shape after that, and proved to be a fabulous, contemporary, non-Eurocentric primer on colonialism. The importance of the sugar plantations in the 1500s for the rise of capitalism was particularly interesting, as well as the role of missionaries and religion in colonialism, and the role of the Russian, Mughal, and Mongol empires in shaping the modern world. Wonderful book.

Another, less a formal textbook but could serve as one, was Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (2015). Very eye-opening, and revealed the economic motivations of the full takeover of the North American landmass by Europeans. Beautifully written and uncovers everything Donald Trump and Kristi Noem doesn’t want you do know about US history. I wept at least once reading it, and you should too.

Besides these, I should also mention Unsettling Truths by two evangelical Christians on the “doctrine of discovery.” Somehow, with four degrees behind me and all the interdisciplinary teaching, I missed that episode where the Pope gives an official mandate to the King of Portugal (and by extension, all Europeans thereafter) to subdue the world for “profit” (oh and “God” too):

…to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens (Muslims) and pagans whatsoever, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all moveable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profit.” (Dum Diversas (June 18, 1452).

Pope Nicholas V authored another document in 1453, the bull “Romanus Pontifex, which “allowed the European Catholic nations to expand their dominion over ‘discovered’ land. Possession of non-Christian lands would be justified along with the enslavement of native, non-Christian ‘pagans’ in Africa and the ‘New’ World.”

This was but two major planks in the platform of religious colonization—and oceans of spilled blood, from one country to the next.

I want to talk about Walter Rodney’s incredible How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Graeber’s mindblowing Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Gerald Horne’s two volumes (the titles do all the talking: The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century and The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in the Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean), books on the Islamic origins of capitalism, and a bunch of others. But, that’s too much to cover here and now.

What’s important to note is that (1) all of these works of quality history confirm the theses of Blaut, and (2) few, if any of then, I am confident, are or will generally be cited in mainstream works on economic history, much less be directly engaged. I think, by now, you know why.

China

One final chapter in my story, which leads to the present.

Frank in Re-Orient kept asserting the primacy of the Asian economy, saying that this period of European dominance is a tiny blip in the long scheme of history, and has already faded away with China’s return to economic dominance now in the 21st century. There’s nothing surprising about “the rise of China.” The Asian economy centered on the South China Sea and Sea of Japan was always massive and active just as it was during the same periods for the Mediterranean basin. But, what exactly was this pre-modern, pre-capitalist, pre-industrial economy like? Why, in other words, was everyone from Christopher Columbus to Adam Smith so plainly aware and interested in the superior Chinese economy?

Because, in a way, nothing is as troubling for the “west is best” narrative than the economic history of China. It directly contradicts countless ideas, aspects, and narratives about European superiority. (That’s the catch with Eurocentrism of the most “scientific” and academic type: it’s actually falsifiable, sometimes easily so.)

This is particularly evident in two books that I’m currently reading. The first is Richard Glahn’s The Economic History of China (Cambridge 2016) and David Lockard’s Societies, Networks, and Transitions (4th ed)—which is actually turning out to be (in my limited perspective) perhaps the most complete and straightforward contemporary non-Eurocentric textbook appropriate for an economic history course. (And thankfully, beautifully written in full color).

I just have to say it: Glahn’s monograph is how economic history proper should be written: engaging, original, clear chronological narrative, empirical when necessary but doesn’t overdo the charts, and weaves together scholarly materials not just for insiders and academics, but for anyone interested in the subject. (The only thing missing is color.) If you’re reading this and confused about what economic history even is or should be, pick up The Economic History of China and let it be your standard to measure the others.

Anyway, it doesn’t take long to realize how contradictory Glahn’s work stands in comparison to anything even remotely Eurocentric. Let me try and give you a brief taste of what I mean. (Brace yourself…)

In the Waring States Period (400s-200s BCE), entire economic treatises were written that addressed rules for crop rotation (p. 96; something typically said to have been first “discovered” by Europeans in the late Medieval period), and debate about how merchants (capitalists) use the market to lord their wealth over the less fortunate—threatening the power of the state (p. 114, 121-25. Cf. 58-60, 78-81). Laissez faire free-marketers debated viciously with (what we now call “Keynesians”) about price controls, government intervention, and even monetary policy (i.e., money supply of the central bank) (p. 122-23). The Chinese economy also boasted highly sophisticated systems of taxation (tariffs, income, and even an asset-based wealth tax) (p. 114), policies governing state intervention in the economy to smooth out cycles and fluctuations in market prices (p. 116), public economic policies based on elasticities (p. 121), legislation on hoarding and price controls (p. 122), and further discourse about which monopolies of the state are beneficial to the economy (pp. 115-125). Economic regulation was strict and thorough. For example, “All persons who travels away from their native place were required to carry passports, and itinerant merchants had to register with local officials to obtain permission to sell their wares…marketplace registers were used to requisition goods for official use and to impose a broader range of legal discriminations (for example, merchants and artisans at times were forbidden to hold government office, or to own arable land)” (p. 92).

Even earlier, around 350 BCE, Shang Yang created a sophisticated system of land redistribution and labor (p. 57-59), and during the Warring States period in general, the economy functioned under four currency zones each based on bronze money (p. 63). The “market laws” text also contain reflection about the benefits of markets—over 2,000 years before Adam Smith penned The Wealth of Nations.

Fast-forward a thousand years to the “Dark Ages” (a more popular Eurocentric myth):

In the seventh and eighth centuries Tang China was Earth’s largest, most populous society, with some 50 to 60 million people and immense influence in the eastern third of Eurasia…Tang China boasted many cities larger than any in Europe or India. The capital, Chang’an…had two million inhabitants. The world’s largest city, Chang’an reflected urban planning, its streets carefully laid out in a grid pattern, the city divided into quadrants, and broad thoroughfares crowded with visitors and sojourners from many lands, including Arabs, Persians, Syrians, Jews, Turks, Koreans, Japanese, Vietnamese, Indians, and Tibetans. Many foreign artists, artisans, merchants, and entertainers, such as Indian jugglers and Afghan actors, worked in the capital, which contained four Zoroastrian temples, two Nestorian Christian churches, and several mosques…. (Lockard, Societies, Networks, and Transitions, 260)

We also begin to learn just how much the Chinese were in pioneers of everything that was, well, supposedly European…

Astronomers established the solar year at 365 days and studied sunspots, and some also argued that the earth was round and revolved around the sun, which many Europeans at the time doubted. Chinese were the first anywhere to analyze, record, and predict solar eclipses. Tang engineers also built the first load-bearing segmental arch bridge. After perfecting gunpowder, an elaboration of the firecracker, by mixing sulphur, saltpeter, and charcoal, Chinese military forces used primitive cannon and flaming rockets to protect their borders or resist rebels. Finally, the Chinese made great advances in printing…Chinese printed the first known paper book, a copy of an important Buddhist text, in 868…

And the Chinese printed a lot of books, and boasted impressive libraries.

The economic dominance and success of Asia led to the European exploration and colonization of the Americas, and countless other movements that created the modern world. This is why Frank and other historians are so insistent that the “rise of the west” rests on the earlier “rise of the east.”

However, as it has already been iterated but must be iterated again, and again, and again: economic historians and economic texts that are stuck in the Eurocentric myth rarely address the economic history of China in a non-superficial way, because it suggests that capitalism’s greatest positive feature—producing wealth, thereby facilitating a “civilized society”—isn’t European, and not even necessarily modern. Somehow, we are supposed to believe that—compared to European standards—a highly inferior, highly inefficient, highly unproductive economy magically fed more hungry mouths than any other civilization in history. (Think about how absurd that assertion is for a second.)

But it’s no mystery how this massive surge in wealth developed: the Chinese simply had the means, the interest, and the cultural institutions to do it. We can pretend they didn’t, and make fun of them for being “despotic,” but that doesn’t matter. (Cue “facts don’t care about your feelings” in the voice of Ben Shapiro).